By Sophie Edelman

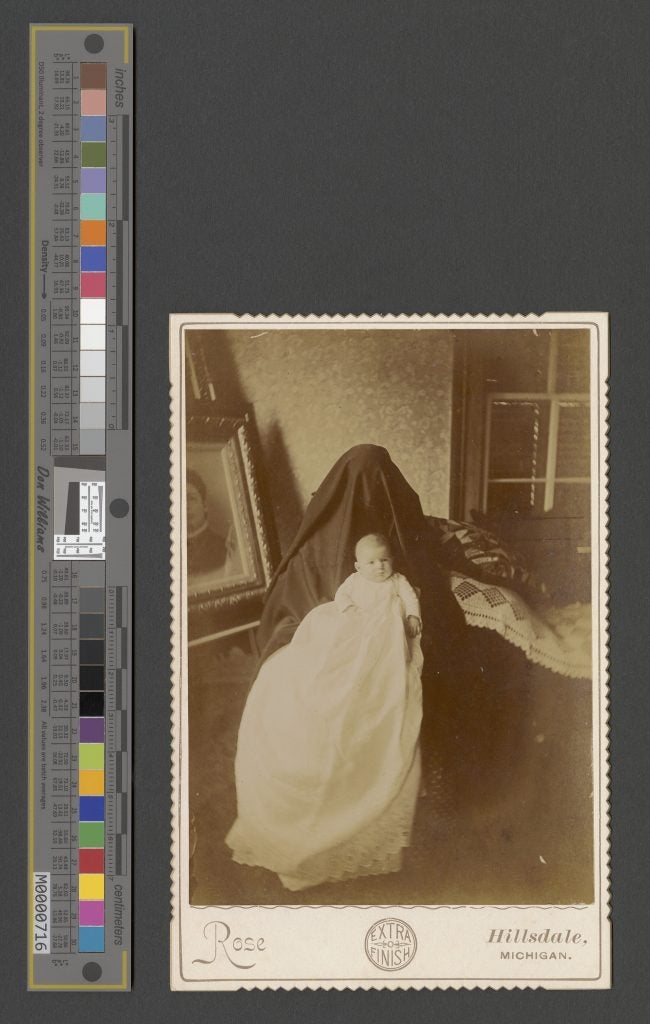

This cabinet photograph, a so-called hidden mother photograph, shows a young white baby wearing a christening gown and sitting on the lap of a figure concealed beneath a blanket. The expression “hidden mother,” according to Susan E. Cook, Associate Professor of English at Southern New Hampshire University, refers to a Victorian photographic trend that was popular in America, England, and continental Europe. By promoting domesticity, Victorianism—named for Queen Victoria (r. 1837-1901)— created the dominant paradigm of an orderly, secure home wherein children were to be indoctrinated with proper values. Victorian mothers hid themselves in their children’s photographs because long exposure times meant mothers had to find a way to keep their children still long enough to be seen while fading into the background themselves. This photograph visualizes Victorian America’s shift in coming to see family less as an economic unit and more as an emotional and moral unit. Hidden mother photographs fit into a longer history of white children as photographic subjects, symbols of purity, and propaganda for seeing childhood less as a means to an end and more as a preservation of innocence.1

The invention of the tintype in 1856 marked the moment in history that photography became mass produced and mass consumed. Until this point in history, portraiture was a privilege of the wealthy.2 The shift from frequent images of family groups to more stand-alone images of infants and children speaks to the affordability of purchasing several pictures.3 Since this photograph is a stand-alone image of a child, the child’s family was likely of the middle class. Stand-alone baby portraits demonstrated the ability to invest money and resources in a child. Because this was unattainable for many immigrant, Black, and Native families across Victorian America, the family of the child in the photograph was likely of non-immigrant status. By observing the socioeconomic status of the child in the photograph, the viewer can deduce her living situation and that of other white, non-immigrant, middle-class, Christian families in Victorian America.

Turning the attention from the child to the obscured individual, professor Susan E. Cook challenges the idea that photographic and literary mothers were literally or figuratively props for the focal point of the representation. According to Cook, hidden mother photographs were extremely widespread and represented several different subtypes. The three subtypes of hidden mother photographs include veiled mothers, mothers obscured as different kinds of objects, and mothers partially or wholly cut out of the frame. Cook suggests that exploring absence as a form in all its complexity can diversify interpretations of the roles of Victorian motherhood. Cook claims that in the process of attempting to obscure herself in the interest of her children, the hidden mother challenges the way scholars look at the family. Additionally, Cook challenges the idea that “hidden mothers” were always mothers. Sometimes, the obscured individuals in hidden mother photographs were fathers, men or women hired by the photographic studio, or family servants such as a nanny, a governess, or an enslaved person of African descent, which was the case of several examples from the southern United States in the 1840s and 1850s. Cook’s iterations of the hidden mother complicate the Victorian maternal ideal.4

References

- “Hidden mother photograph,” date unknown, David V. Tinder Collection of Michigan Photography, William L. Clements Library, Ann Arbor, Mich.

- Shill. (n.d.). Hidden mother tintypes and the performance of the self. CU Scholar. Retrieved October 8, 2022, from https://scholar.colorado.edu/concern/graduate_thesis_or_dissertations/n009w359p

- “Hidden mother” portraits reveal a historic moment in American photography. Ohio University. Retrieved October 8, 2022, from https://www.ohio.edu/research/communications/hidden-mother-portraits-reveal-historic-moment-american-photography

- Cook, Susan E. 2021. “Hidden Mothers: Forms of Absence in Victorian Photography and Fiction.” Nineteenth Century Gender Studies 17 (3): 1–25.