By Ava Coon

“White slaves” photos, as historians call them, were used to campaign for the education and ultimately the uplift of enslaved African Americans. The photographs were taken in New Orleans to encourage white northerners to support the Union army because many northerners rejected the draft at this time. By using white slaves to appeal to northern white audiences, photographer Myron H. Kimball galvanized support for the abolitionist movement. The campaigners used light-skinned children because of the prejudice against darker-skinned ones, as white audiences associated innocence and purity with whiteness. Through an analysis of these photos, the themes of gender, childhood, and race become prominent. The promotion of education and the use of white-looking children were effective in supporting a movement towards anti-slavery.

In the photo of Rebecca, Augusta, and Rosa, the abolition campaign focused on white-appearing children rather than adults with hopes that their whiteness and childhood status would prompt northern whites to question the ethics of slavery. They also used well-dressed children, mainly girls. The role of gender in these photos is important because it shows us how girls were understood as especially vulnerable and in need of protection. The photo shows us how race, gender, and class status were fundamental to defining someone’s position within antebellum society. Children are seen as pure, innocent, and vulnerable, and using young girls has the added advantage of appealing to paternalism to persuade white men to support the Northern draft. According to Kathleen Collins, darker-skinned children were only used in photos when their “youth and piccaninny charm posed no threat to the status quo” (Collins, 189). By doing this, the leaders of the campaign successfully achieved their goal of getting the northern white American public to question the ethics of slavery, but did not do much to challenge racial privilege and inequality.

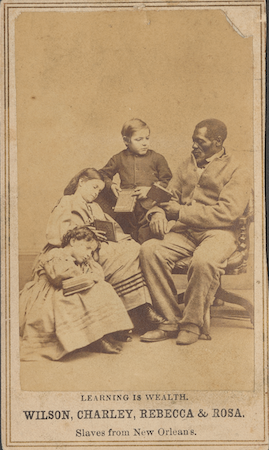

There is a huge emphasis on the push for education in these photos, especially this Learning is Wealth one. The primary education system for African American children was not sufficient, especially during this era. The segregated schools were subpar, often lacking adequate sanitation, weatherproofing, and curricular resources for children and teachers. Schools were not even specific schoolhouses; rather, they were often transformed from “cabins, sheds, and unused houses” that were “roughly repaired, [and] fitted with cheap stoves” (Collins, 187). The teachers were recruited through missionary and abolitionist groups, and therefore did not have formal teaching credentials. Kathleen Collins writes, “money [for better schools] could be raised if Northern abolitionists could see actual photographs of the emancipated slaves who were being educated in the New Orleans schools” (Collins, 188). They used enslaved children for this reason, especially ones that white audiences would deem sympathetic based on their race and gender.

The emphasis on education for African American children was a successful tactic used for racial uplift. The goal of these photos was to improve educational opportunities for formerly enslaved children, and through the use of “white slaves” photographs, support was generated. The education system had massive improvements, such as changing the location from sheds to actual classrooms and changing the educators from mere volunteers to formally certified teachers. The photos were sold and all of the proceeds were donated to the education of colored people in the department of the Gulf, under the command of Maj. Gen. Banks. The use of white-looking children generated the support needed for these wanted changes to become actual changes, leading to some degree of racial uplift through education.

Citations:

“Rebecca, Augusta & Rosa, Emancipated slaves, from New Orleans”. 1863, Kimball, Carte de visite photographs, Weld-Grimke collection, William L. Clements Library, Ann Arbor, Mich.

“Learning is Wealth. Wilson, Charley, Rebecca, and Rosa, Slaves from New Orleans”. 1864, Kimball, Carte de visite photographs, Weld-Grimke collection, William L. Clements Library, Ann Arbor, Mich.

Kathleen Collins, “Portraits of slave children,” History of Photography 9:3 (1985): 187-210, DOI: 10.1080/03087298.1985.10442287.

Mary Niall Mitchell, “‘Rosebloom and Pure White,’ or So It Seemed,” American Quarterly Vol 54, no. 3 (Sept. 2002): 369-410.