By Margaret Watson

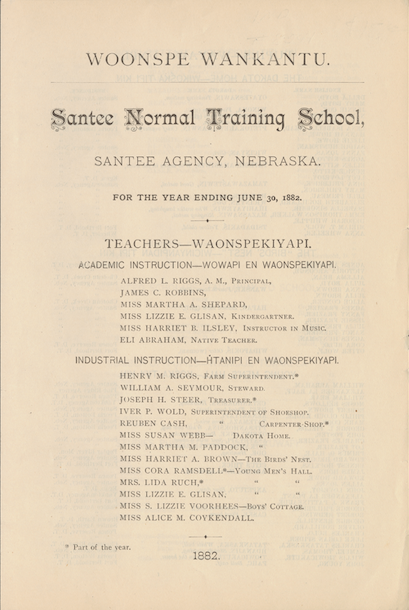

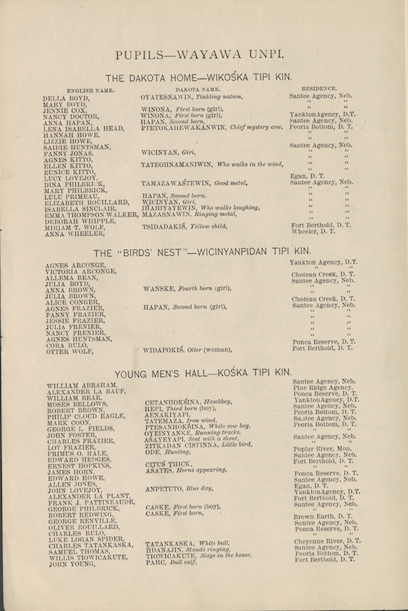

The Santee Normal Training School record of students’ English and Dakota names from 1882 unveil the way that Native American people were forced into assimilation in the late 19th century. It offers insight into the way white settler gender roles were forced upon Native children through the act of renaming as well as by showing us the classes students took at the training school.

The list was produced in Santee, Nebraska in 1882 by white teachers and administrators running the training school. The document contains names of teachers and students, as well as subjects that were taught at the school. Subjects included more traditional subjects like arithmetic, English Reading, and Bible History, but the boys and girls were also taught different types of “industrial work” in their time at the training school. Boys were put in shoe shop, carpenter-shop, and farm classes. Girls had their own section in which they were taught how to cook, clean, and sew. The Dakota children were also given new English names, which are printed in this source. This is a form of cultural erasure and shows us how little regard there was for the Dakota people’s Native identities. Documenting how harsh these boarding schools were has historically been difficult because of the methods school administrators used to cover up abuses.

Jane Griffith highlights how these boarding schools contributed to the erasure of Indigenous languages and the different ways the Indigenous people resisted this form of assimilation. Griffith argues that the real reason for the attempt to eradicate Indigenous languages was access to land, and not spreading the gift of English, which is what many documents produced by white teachers and administrators at Native boarding schools claim. Griffiths’ use of survivor testimonies offers an important perspective on how Native students experienced and resisted linguicide and cultural erasure. It wouldn’t be possible to see this if official records were the only thing looked at. Griffith uses survivor accounts to confirm how poorly the Indian boarding schools treated their students. She shows how the stories of these Indigenous people were suppressed by the government. Griffith’s findings affirm how the English language was forced upon the Indigenous children in these boarding schools. While we don’t know the stories of the children listed in this document, or even whether they survived, we can imagine how they might have resisted the erasure of their Native language and culture by looking to Griffith’s survivor testimonies.

Citations

“Woonspe Wankantu: Santee Normal Training School: Santee Agency, Nebraska, for the year ending June 30, 1881,” [Santee, Nebraska: Santee Agency], 1881.

Jane Griffith, “Of linguicide and resistance: children and English instruction in nineteenth-century Indian boarding schools in Canada,” International Journal of the History of Education, Vol. 53, Issue 6 (2017).