Interweaving narrative, metaphor, and reflection with overarching questions and social theory, Carmen Maria Machado’s memoir, In the Dream House, is an account of Machado’s harrowing experience in an abusive relationship. More than that, In the Dream House examines the unique circumstances that arise from abusive queer relationships compared to abusive heteronormative ones. She tackles the mental gymnastics that victims of domestic abuse have to perform just to survive and the ways she has grappled with coming to terms with her situation. There’s also the added layer of manipulation introduced by the pressures of upholding the pristine image of the model minority. She navigates that pressure in such a way that any reader—queer or not—will understand the feelings she lays bare. And although the relationship central to In the Dream House is woman-with-woman, Machado makes sure to clarify that hers is only one of countless accounts, each one valid in its own right.

From Amazon

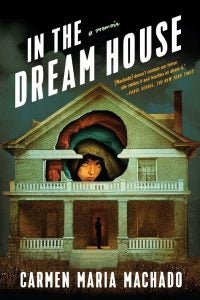

In the Dream House sets the tone immediately, beginning with the cover. The illustration of the house on the front cover evokes the fear implicit in abusive relationships. It has a hole knocked out of the bricks, vines crawling up the dilapidated eaves, and a backdrop of stormy cloud cover behind the house. Three epigraphs interspersed throughout the first few pages read like the opening credits to a somber movie. The dedication page is at once an offer of help and an ominous warning: “If you need this book, it is for you.”

Following the surrogate credits, Machado gets to the point. She includes only as much exposition as is necessary. This includes an explanation of the Dream House, a place as real as it is a metaphor for the abusive relationship; her life in Iowa City pre-Dream House; and her first exposures to lesbianism. That’s all that comes before Machado introduces the main antagonist. Or rather than “main antagonist,” perhaps I should say the person who could be considered by many readers, including myself, to be the main antagonist, and by others, perhaps including Machado, just one of many “hurt people who hurt people” (232). This person is never named. She’s referred to only by she/her pronouns or as “the woman in the Dream House.”

Finally, wrapped up with all this exposition is Machado’s introduction of the main character. The main character is her. But the main character is also you.

The second-person perspective stands out to me as the single most important element of this narrative. Machado starts in first-person, then shifts into second-person when the relationship with the woman in the Dream House begins. Aside from a few moments of personal reflection outside of the confines of the relationship’s story, the narration remains in second-person until the relationship ends, and even a little beyond that. It’s a useful way to contain the anecdotal moments.

From The New Yorker

It’s also a useful way of putting the reader in Machado’s shoes. When someone in an abusive relationship brings it up to a person they trust, it’s so often met with a response along the lines of “why did you stay”/“how could you let someone treat you like that”/“I would never let someone do that to me”/whatever else people seem to think is an appropriate response to someone confiding in them. This is especially the case for relationships where the abuser uses emotionally or mentally manipulative tactics instead of physical ones, as was the case for Machado.

The second-person narration cuts out that middle step. Machado forces the reader to experience a pseudo-firsthand account of the horrors she had to endure during her relationship—but she also develops the very real love and affection that was mutually present between her (you) and the woman in the Dream House.

This development has the effect of giving the reader a personal establishment of the relationship from the real beginning, not just when the abuse started. It’s easy to boil down an abusive relationship to the abuse and call that the only takeaway. In reality, though, relationships are never that one-dimensional. In the first fifty or so pages of In the Dream House, the reader experiences the intoxicating headiness of an early relationship. You feel the joy of seeing your person after a week apart, the flutter when you catch them staring at you with love in their eyes, the warmth of waking up next to them in the morning. It’s all there and it all feels like a fairytale.

Like a fairytale, though, there’s a twist coming. And like so many fairytales don’t have happy endings, neither does this relationship.

Another intriguing aspect of In the Dream House is the many references to Stith Thompson’s Motif-Index of Folk-Literature. The footnotes sprinkled throughout the text draw parallels between Machado’s experiences and fairytale motifs, drawing attention to how unbelievable some of those experiences seem—but that’s part of what makes abuse so horrifying. For example, Machado describes a conversation between you and the woman in the Dream House after she dismisses the idea of going to therapy:

“‘You threw things at me,’ you say. ‘You chased me. You destroyed everything around me. You have no memory of any of it. Doesn’t that alarm you?’”

Thompson’s motif-index is referenced in a footnote during the exchange: “Type C411.1, Taboo: Asking for reason of an unusual action” (150).

And suddenly, fairytales don’t seem so outrageous after all.

My only qualm with the references to the motif-index were that I would have liked to see them included earlier. The first one wasn’t used until page 21, and while that may seem pretty early, I believe the motif-index should have been established as a device from the very beginning. At first, I was unsure whether they would continue to be used beyond the first few references, but in that regard, Machado did not disappoint; the footnotes can be found at least every few sections. Some citations made more of a mental leap than others. The ones that made the least sense to me were few and far between, though, so I was mostly happy with—and often surprised by, in a good way—the ones I read.

By the end of In the Dream House, some of the ideas Machado introduces and then returns to over the course of the book become repetitive. In one instance, an entire section toward the end, while beautifully written, is essentially a briefer restatement of what the story has already shown the reader. Often, revisited ideas are further developed each time Machado brings them up again. For the most part, then, repetitiveness isn’t actually an issue. Because of the rare instance of tedious writing, though, those moments stand out even more. That’s what makes them so easy to identify.

Machado is now in a happy, healthy relationship. Pictured here with her wife. From Twitter

On the other hand, the book’s prose is gorgeous. The writing is familiar, yet unique; the most poetic sentences make me feel like I’ve finally remembered something I didn’t know I forgot. As someone who has struggled through an abusive queer relationship, Machado puts to words feelings I’ve never before had the language to express. My favorite line is on page 55: “By the time you’ve wound out of the mountains and gotten back to a freeway, the bite of the fight has sweetened; whiskey unraveled by ice.” And the sickly kindness of this line on page 129, which comes after screaming and death threats and a break-in through the locked bathroom door, stuck with me long after I’d finished reading, like the hull of a popcorn kernel lodged in the back of my throat: “‘Why are you crying?’ she asks in a voice so sweet your heart splits open like a peach.’” This is what it means to be ensnared in the jaws of an abusive relationship. Machado captures it perfectly.

***

About a quarter of the way into the book, you meet the woman in the Dream House’s parents for the first time. Her father’s behavior and the interactions between her parents are one of the first indicators of the dangers to come in the relationship. As the reader, it hurts to see her parents, especially her father, and realize she was conditioned to be the way she is. It hurts because it makes you see the cycle and realize that it’s not entirely her fault even though you want so badly to throw all the blame on her.

But later, Machado recalls an aunt of hers, who “was known to fly into unpredictable rages” that left her crying, afraid, or some mixture of the two (a footnote in this section aptly refers to this relation as “cruel aunt,” Type S72 from the motif-index) (70). Machado’s mother explained away her aunt’s behavior as being caused by the pain of endometriosis. Machado comments that later, when she was also diagnosed with endometriosis, Machado “managed to get through the worst of it without screaming at small children, or anyone for that matter” (71). This despite the fact that she endured torment from her aunt for years.

The narrator’s response to the “cruel aunt” shows us that, ultimately, it’s we ourselves who are in charge of our fates. We control how we react to strenuous situations and how we treat the people around us. No matter how sympathetic the woman in the Dream House’s parents may make her seem, Machado herself is a reminder that we hold the reins in our hands. In the Dream House tells us we can come out on the other side of a difficult experience and decide what to make of it. Let that be a message of hope to all its readers, and let its readers not forget: If you need this book, it is for you.