I don’t have a favorite book. Yes, I have a solid group of four or five that read over and over again, but I’ve never been good at picking one solid favorite. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince, however, is one that keeps appearing in my life whenever I seem to need it the most. I am immensely grateful to whatever god of stories is out there for putting this book in my life.

I don’t know where my first copy of Little Prince came from. I know it had lived on the bottom shelf of my childhood bookcase for years, and I know I must have read it at some point as a young kid. I think I remembered it as a fairy tale with pretty pictures, but not much more. I “rediscovered” it while emptying said childhood bookcase when I was thirteen. My family was moving from the old house on the hill I had grown up in right here in Ann Arbor, to an even older farmhouse in the tiny town of Ida, about forty-five minutes away.

At the time of packing away my books for that first move, I was optimistic about the whole affair. Yes, I knew I would miss my friends and my middle school here in Ann Arbor, and I knew no house would ever stand up to the one I grew up in, but I was still excited. We were moving to a farm! I could have animals! The pain of leaving was discarded in favor of imagining getting goats and filling barns with as many cats as I wanted.

The Little Prince is obstinately considered a book for children, but the story is one perhaps not fully appreciated until later in life. When I rediscovered it on my bookcase as a newly-turned teenager, at a time when I was eager to fully separate myself from what I saw as “childish,” I fell in love.

The story begins with our narrator talking about all the drawings he used to make as a child, illustrations that adults soon persuaded him to give up on in favor of “geography, history, arithmetic, and grammar.” With his career as an illustrator thrown away at the young age of six, the narrator decided instead to become an aviator. He travels the world, meeting all manner of “serious people” and grown-ups. Then, he crashes in the Sahara Desert.

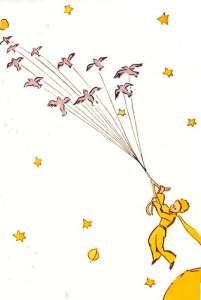

The Little Prince could be described as a book about loneliness. It speaks of the urge to feel connected to the people (or foxes and roses, in this case) around us, as well as all the ways we fail in doing so. The Aviator, however, is not as physically isolated as one might expect. Stuck in the desert, surrounded by miles and miles of sand, he is discovered by a little boy. A prince, to be exact. The Prince claims to be from an asteroid that contains three volcanoes, one extinct, a rose, whom he is in love with, and some baobab seeds, which will destroy his tiny planet entirely if allowed to grow too big. After a long journey between various planets, in which he was aided by “the migration of a flock of wild birds,” the Prince has found himself on Earth. Together, he and the Aviator travel the desert, and the respective stories of each are revealed to the reader.

Sitting on the floor of my childhood bedroom, tucked into an alcove surrounded by boxes and books, I fell in love with the Prince. The whimsy embedded in every single page and illustration spoke to me in a way I had been missing since growing out of “kids” books, and I remember being shocked that I hadn’t remembered the story better. I also cried over it. In telling of the journeys of the Aviator and the Prince, two tales of longing are woven together. The Aviator is desperately trying to get home while simultaneously mourning his childhood, as revealed to us through his retelling of the Prince’s story. The Prince himself, who is in part characterized by his eternal childlike wonder, begins the story by simply wanting a drawing of a sheep. By the end, however, as we have learned about all the ways his journey has led him to the Aviator, the Prince just wants to go back to his planet and rose. I knew it seemed like more than a kids’ book when I read it as I packed, at an age when I was eager to put away “childish” things, and I put it into a box, knowing I would be digging it out again soon.

To call The Little Prince anything but a bittersweet story would be a mistake. There’s an emotional depth to it that goes beyond what most children’s stories achieve. This is not to say the book is a complete downer, but there’s a certain sense of melancholy inherent in the Prince’s story. The first creature he meets upon his arrival on Earth is a snake, who tells him the loneliness of the desert is something also found when surrounded by people, highlighting the prince’s solitude even as he meets everyone from lamplighters to kings during his travels. Although he has learned something from all the people he has come into contact with, there is no real sense of connection with any of them.

The book’s melancholy can also be seen in the theme of leaving — something that seems to happen time and time again during the Prince’s story. There’s the rose, left alone on the tiny planet because the Prince was “too young to know how to love” her, and a fox, whom the prince became friends with briefly before leaving alone. While being left behind, however, the fox delivers one of the book’s most quoted lines: “One sees clearly only with the heart. Anything essential is invisible to the eyes.” These profound lines are woven throughout the story in a way that both lift the sad moments while grounding the more fantastical ones. This adds a pensive weight to the story, and reading it almost feels more like a philosophical guide than a simple fable.

Despite my initial excitement, the move to Ida was a rough one. Our house was being renovated, and it wouldn’t be ready for at least a year. The box containing my copy of The Little Prince got put into storage, and my family moved into a rental house. While having animals was fun, I found myself missing Ann Arbor more than I’d expected. My new school was nothing like what I’d hoped for, and it was a long adjustment period. It was the classic “new kid has a rough time” story, exaggerated by the fact that Ida is the type of town to only have a single streetlight. I felt completely isolated in my tiny school surrounded by cornfields, and no passing flock of birds was coming to help me escape.

By the time he meets the Aviator, the Prince has been on Earth for almost a year. As the Aviator becomes closer to fixing his plane and making it home, the Prince’s tale of the journey that led him to this point draws to a close. However, his travels aren’t over yet. While he’s told the entire story of how he ended up in the Sahara, there’s one last place the prince wants to go: home. Back to his rose and to his planet, which may or may not have been destroyed by baobab seeds by this point. However, there are no more flocks of birds to help the prince get home either this time. Instead, he recruits the help of the snake who had initially welcomed him to the desert, a snake with poison “more powerful than a king’s finger.” This snake promises he can help him get back to his rose, but his Earthly body is too heavy. He’ll have to leave it behind if he truly wants to go home.

After a year, the house my family was renting was sold. Our “actual” house wasn’t done being renovated yet, and, as Ida is not a place filled with houses waiting to be rented, this posed an issue. With nowhere else to go, my family moved into an RV we parked in the driveway of the half-gutted house. While we only had to stay there for a few months, they were probably the hardest months of my life. I was a high school freshman, at the age where one is profoundly embarrassed by everything imaginable, and I was stuck in an RV with no privacy. The continuing struggles with homesickness and dealing with a new school weren’t helped by having to drive across town to my grandma’s every time I wanted to use an actual bathroom. I used to sneak out at night to walk around, a remarkably easy task given that the couch I slept on bumped up against the door every time I rolled over. I don’t remember a lot from this period in my life, but I do remember wandering around at night, wishing I was anywhere else. The Little Prince remained locked in a storage unit somewhere.

The Prince considers the desert beautiful, because “somewhere it hides a well.” This single piece of good is enough to offset all the dangers associated with being stranded. Before he leaves for home, the Prince tries to convince the narrator of something similar. “When you look up at the sky at night, since I’ll be living on one of them, since I’ll be laughing on one of them, for you it will be as if all the stars are laughing,” he says, as if that is supposed to be enough to comfort the Aviator after his “death.”

We eventually were able to move from the driveway into our actual house. Things got better. They weren’t great, but I actually remember most of those later years in Ida. I made more friends and I joined the after-school drama club. The goats won first place at the fair. I still missed my old home deeply, but I began to make peace with farm life. I still hadn’t figured out where my copy of Little Prince had disappeared to, and I mentioned missing it to a few people. Multiple people decided to get me the book for Christmas one year, giving me two copies to replace that original one that I can now admit is lost for good. Maybe it’s for the best, as having multiple copies means I can shove this book upon all my friends.

The snake does his task, biting the Prince’s ankle, and the Aviator is alone once again. Surprisingly, the idea of laughing stars seems to work. The Aviator gets his plane working, and he makes it home a changed man. While he’s initially sad about the Prince, he is at least partially consoled. As he says, “I knew he did get back to his planet because at daybreak I didn’t find his body… And at night I love listening to the stars. It’s like five-hundred million little bells…” Despite all he had to learn and leave behind, the Prince has made it home in one way or another. And the Aviator is happy for his strange little friend.

My parents got divorced about a year after I’d received my new copies of Little Prince. My dad moved out, and I was once again in transit. He had moved back to the outskirts of Ann Arbor, and suddenly every other weekend I was packing my stuff to go visit him. Despite technically being in Ann Arbor, his place was far enough away from anything I recognized that it didn’t really feel like coming back. I didn’t have my own room or any of my own possessions there, and it was far enough away from any bus line that there was nowhere for me to actually go. Although I was closer than I’d been in years, I still wasn’t home.

I ended up bringing a copy of the book with me most weekends I spent at my dad’s, choosing to keep it in my backpack rather than leaving it there. I’d flip through and reread sections almost obsessively. It was sadder than I’d remembered. I hadn’t realized enlisting the snake to “help him get home” was effectively the Prince choosing to die when I read the scene at thirteen. I didn’t pick up on the constant theme of leaving people and places while looking for home. I hadn’t recognized the loneliness the Prince carries with him, surrounded by people yet never quite relating to them.

I gushed about this book to all my friends in Ida. I lent my books out time and time again. I made plans to get the illustration of the flock of birds tattooed on my arm in the future.

I still missed Ann Arbor.

Then, college admissions came around, and I realized my urge to get as far away from Ida as possible was stronger than my desire to truly go “home” to Ann Arbor. It felt like coming back would be more like trying to recreate my old life than starting something new, like the Prince going back to his rose without having learned anything new about how to love. I thought leaving the state would be the first step in finding a new home, like the Prince shedding his body in favor of traveling the stars.

As it turned out, I didn’t make it out of state. I brought all my mixed feelings back to Ann Arbor, alongside a copy of Little Prince. Luckily, the past two years at Michigan have been better than I ever let myself believe possible. I do still wonder what it would have been like to go somewhere completely new, but as it turns out, there’s a big difference between living in Ann Arbor as a kid and experiencing it as a student.

I’m now halfway through my time in college, and I still don’t know what I want to do. As it turns out, having all your goals focused on leaving somewhere means you don’t actually know where to go once you’re out. I feel like I change my major every week, and I have no real plan for the future. I’d written my college application essay about all my conflicting feelings about the idea of “home,” and I’m still no closer to knowing where I want to be. I feel like I’m constantly moving between Ida and Ann Arbor, and it hardly seems worth unpacking at this point. However, I was given a 75th-anniversary edition of Little Prince recently, and I’ve taken to leaving a copy in all my various “homes.”

I still don’t know where that original book ended up, but I think I’m okay with not finding it. Maybe some things don’t need me to come back to them. Maybe moving forward once and for all is the best course of action. At the end of the day, maybe the point of The Little Prince isn’t that the Aviator and the Prince both go home at the end, but that they left in the first place. Maybe it’s less about being lonely and missing home and more about making the connections that will make us feel at home wherever we are. I know I’m still struggling to learn these lessons, but I know this book will find a way of showing up in my life whenever I need it.