If you’ve ever taken a creative writing class in college, you’ve probably heard the same thing I’ve grown to expect on the first day of any given writing class that’s creative in any respect: No Fantasy or Science Fiction Work. The professor might give some long-winded speech about why fantasy and science fiction are too expansive or not literary enough for short fiction. They might close by warning against even attempting those kinds of writing in their class. Or it might be a clause written in fine print and buried in the pages of the syllabus amid other restrictions like those warning against plagiarism or discrimination. Sometimes, students will be encouraged to talk to the professor before writing fantasy or science fiction. And there’s the rare occasion where those genres are allowed or even, in the scarcest of cases, encouraged.

Of all those cases, it seems like the most common one by far is the case when fantasy and science fiction are completely barred from the creative writing classroom.

Taken from https://www.rd.com/culture/the-best-fantasy-books/

I’ve heard rationales for disallowing fantasy and science fiction writing from creative writing classes that range all over the spectrum of logic. One professor simply didn’t want to read that kind of work because they “had students write fantasy and science-fiction before, and it had never been good.” In a way, this makes sense. I can imagine that, as a professor, it must be difficult to have to read page after page of poor writing. If the worst of that writing always happened to be fantasy or science fiction, it’s natural that a bias against those genres would arise. The conclusion may be, as it was for my professor, to ban fantasy and science fiction from the class to prevent that situation from happening.

But if whole genres could be banned from writing classes, or any kind of class that involves writing, then I’m sure the staple of academia—the research paper—would be long gone by now. I’ve never met a professor who’d never read a shitty term paper. I don’t need to ask any of them to know that. It’s just a given. Some people come into college barely knowing how to write, and some, while they have the strongest writing facilities, just can’t seem to get to the meat of their paper, instead dancing around their argument with flowery language until the point of the writing is indiscernible.

And that’s okay, because that’s what school is for. We come here to learn. We take classes in subjects many of us have never taken before, including creative writing, so that we can gain experience in the topics we’ve always been interested in but have never had the chance to develop. Of course my English professor, who teaches creative writing, would’ve seen some terrible fantasy writing from students in the past. If substandard writing hasn’t offed the research paper, though, then why does that mean fantasy and science fiction should never again be brought into the classroom?

Then there’s the argument that once a student had demonstrated they can write well in a more palatable genre, say, literary fiction, then they could move on to writing in a more unconventional genre, like fantasy or science fiction. This is a well-meaning approach to allowing fantasy or science fiction to be written for a creative writing class because it doesn’t close off the option entirely. It certainly improves on the model of not allowing any fantasy or science fiction just because a few students in the past wrote subpar genre work. For this policy, the idea was that students needed to be able to show mastery of their writing without having to worry about the hallmarks of fantasy and science fiction, including worldbuilding, magic systems, and other elements of fantasy and science fiction that just aren’t broached in literary fiction. That could be considered a fair requirement.

Taken from https://abstract.desktopnexus.com/wallpaper/2251028/

When I applied to write an honors thesis in the genre of fantasy to a selection committee that included the professor I had for that class, however, I was turned down on the basis that no professor wanted to take on a thesis proposal that didn’t have the potential to receive honors. In other words, none of the professors on the selection committee believed that a thesis comprised of fantasy work was worthy of honors.

The thesis lacked the usual barriers to writing thorough, strong fantasy that exist in short fiction classes. It was to be up to 100 pages long, and I could divide the work into however many or few stories I wanted. If my proposal had been accepted, then, it was perfectly possible for me to write one long piece with well-developed worldbuilding and a bulletproof magic system alongside the requirements of strong literary fiction, like complex characters, compelling storylines, and tight language.

So what was it about my thesis proposal that resulted in professors not seeing potential in it?

I have to think that it was the fact that the proposed genre was fantasy that tanked my chances at writing an honors thesis. Considering the attitude my professor purportedly held toward fantasy and science fiction writing in my class, I was surprised to receive a rejection. At the very least, because of what I perceived to be her open-mindedness, I thought she would consider being my advisor for the project. Maybe she did; I, of course, don’t actually know what went down within the selection committee, so I can’t blame my professor for a majority decision.

In the end, it seems like long-lasting prejudice against fantasy and science fiction in the English world won out against my thesis proposal. I was offered to write personal essays for my thesis instead. Dejected, I politely turned the offer down.

I read once in a Tumblr post (a site that affords, among piles of flaming garbage, the occasional gem of writing—perhaps the most apt metaphor for the argument I’m attempting to make here) about a student whose creative writing professor tried to pick on them for reading Terry Pratchett, calling the novel the student brought to class “‘popularist fiction,’ like somehow being popular and easily accessible made it less inherent in intellectual value.”

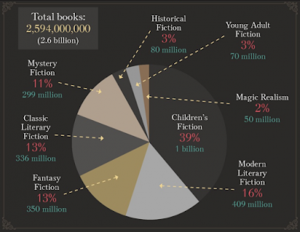

Taken from https://publishedtodeath.blogspot.com/2017/11/what-are-most-popular-literary-genres.html

The post went on to explain how this sentiment was total nonsense, citing the work of Shakespeare and Dickens as examples. I agree. Just because something is popular doesn’t mean it doesn’t have worth. In fact, shouldn’t we be excited about work that gets people reading, no matter the genre? According to a statistical report on bookadreport.com, fantasy and science fiction novels are collectively making the fourth-highest amount of money out of all genres (following romance, crime/mystery, and religious/inspirational). In another statistic found on publishedtodeath.blogspot.com (taken originally from Statista), fantasy and literary fiction had equal ratings in popularity. At the very least, that seems to warrant more respect from fantasy work in the writing community than that work currently receives.

Although money and popularity aren’t the only factors at play, it seems like popular genres can and should be used to communicate ideas to our fellow humans, just like Pratchett wrote about humanitarian issues in the stories taking place on the Discworld. I felt that I had something to contribute by writing about the same themes I could write about in literary fiction in fantasy pieces. Because of the stigma the English world holds toward fantasy and science fiction, though, that was never an available option.

We see the importance of fantasy and science fiction as genres of writing every day. We see it in the course devoted entirely to the fantasy genre here at the University of Michigan (English 341, if you’re interested), which only grows in popularity every semester. We see it in the tight short stories of science fiction authors, like Ted Chiang’s “Story of Your Life,” the short story the feature film Arrival is based on. The short story holds all the poignancy and dimension of the movie, but packed into thirty-some pages. That takes skill, people. We see it in an entire generation of people who read Harry Potter growing up, and who were shaped by that experience, and who were encouraged to keep reading by their fascination with the series. Let no one ever say that fantasy and science fiction don’t hold value simply because they’re not the current staples of collegiate English programs.

Let me say now that I don’t hold it against any of my professors for taking this stance on fantasy and science fiction writing in the academic world of creative writing, no matter the degree they take that stance to. I understand that this is a deeply ingrained facet of creative writing. I hardly expect every scholar to do away with the structures that have worked for college English for so long. I also don’t necessarily blame anyone for believing that fantasy and science fiction don’t belong in creative writing—until now.

Now, I’m challenging every English professor—and English student!—who reads this piece to think critically about the biases they hold toward fantasy and science fiction writing, and to brainstorm a way to allow fantasy into the academic world that suits both their requirements for a good piece of writing and the student’s requirements for a good education. I have no doubt that once people are able to do that, the English world will be able to take a step in an exciting new direction: a direction that not only allows for but encourages the development of previously neglected genres. I can’t wait to see the English programs, concentrations, fellowships, and whatever other opportunities are made available to the creative writers of the future, with focuses in fantasy and science fiction alongside the traditional focuses we’re used to today.