by Cleo Randall & Tsumari Patterson

The Civil War was fought between the Confederacy and the Union. The Confederacy, which consisted of 11 southern states, separated from the rest of the United States (the Union) to preserve their rights to enslave people. The Union consisted of the remainder of the states that did not necessarily seek to end slavery itself but wanted to unify the growing United States. The federal government established the U.S. Sanitary Commission– a soldier care and relief program– when the Civil War took a turn from “mass warfare into total warfare.”[1] Thousands of civilian doctors and nurses volunteered to support the Union cause and provided a lot of help necessary for the eventual victory of the Union. These volunteers helped with everyday healthcare needs of sick and wounded soldiers, including amputating soldiers’ limbs or nursing soldiers from the verge of death.

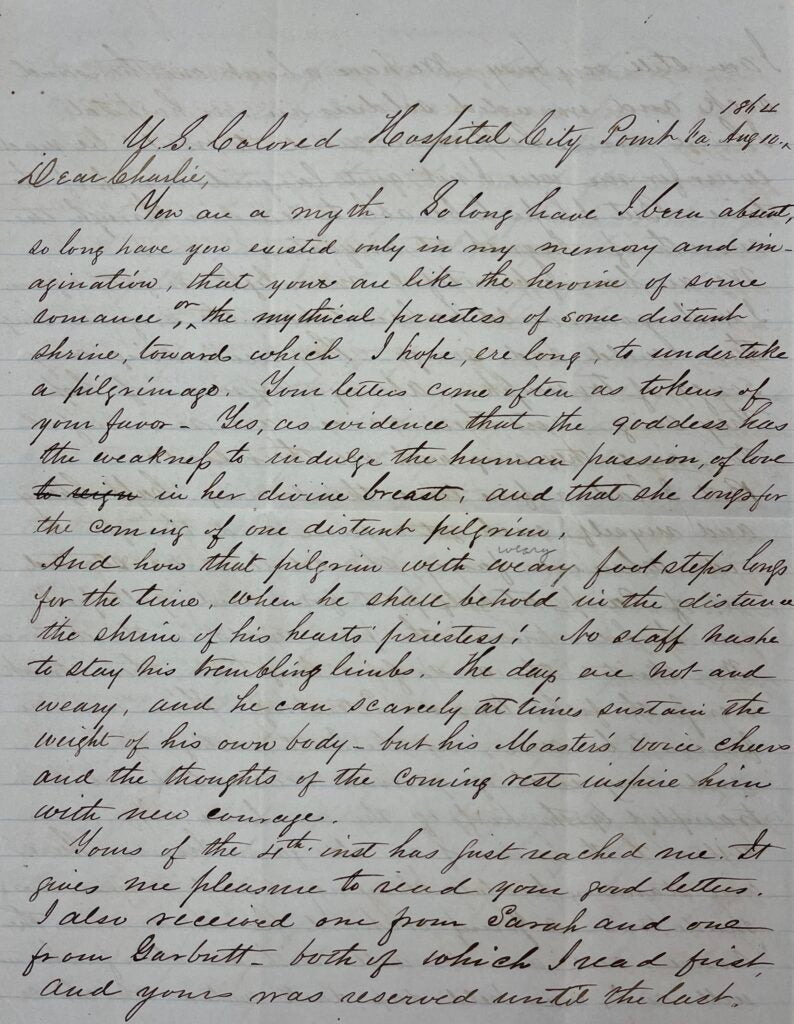

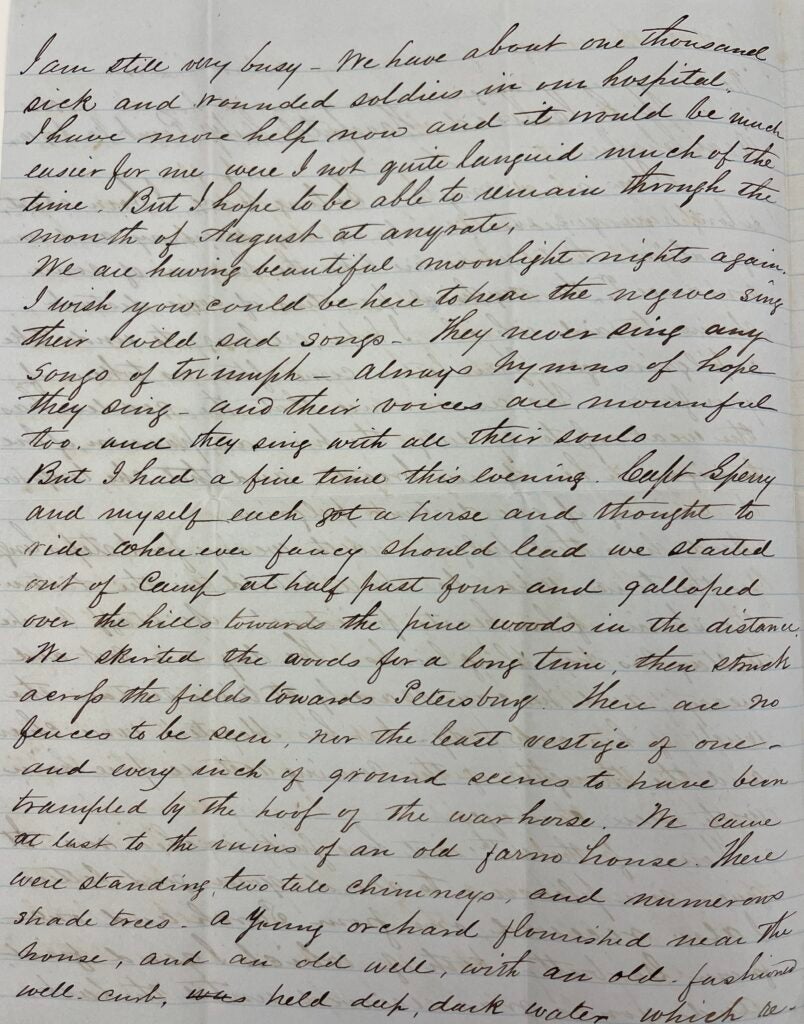

Samuel Ferguson Jayne, who studied medicine at Harvard, left his education to work with the U.S. Sanitary Commission. Jayne was based at the U.S. Colored Hospital at City Point, Virginia, which treated African American soldiers who fought in the battles at Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor, and the Battle of the Crater (Petersburg) through the summer and fall of 1864. In this letter to his fiancée, Charlotte, Jayne reveals that behind the scenes, African American soldiers who were putting their lives on the line for the Union continued to experience discrimination and mistreatment. He also reveals that wounded soldiers in the hospital sang “hymns of hope” as acts of resistance.

Some free African American men joined the Union army in hopes of finally being recognized as equal and productive citizens. Some enslaved men had run away from their enslavers’ plantations or houses and had joined Union lines as contrabands. Other African American soldiers were paid to take white soldiers’ places. The Confederacy and then the Union established a draft system for white men, but those wealthy enough could pay others to fight in their place, which accounted for some of the African American soldiers who fought in the war. According to Historian Andrew T. Tremel, some abolitionists like Frederick Douglass advocated for African Americans to serve in the military. They “hoped that this demonstration of patriotism and manhood would ease racial tensions and open the door to equal rights as citizens.”[2]

Jayne’s letter provides insight into race relations in the hospital. He expresses his concern for the Black soldiers who were not receiving proper health care. “We have had to almost fight the doctors to get them to treat the colored men decently and to find them proper attention,” he writes, revealing that doctors working at the caretaking facility for African American Union soldiers were still incredibly racist.[3] The Sanitary Commission was there to provide better care. However, Jayne himself promotes racist ideas about African American soldiers: “I do not think it would be exactly fair to obtain a negro for a substitute…in all modesty, they do not make as good soldiers as the whites,” he writes. This letter demonstrates that African American soldiers were not only fighting for their chance at equality during the Civil War, but they were actively resisting the pervasive idea that African Americans were inferior to their white counterparts.

Scholar Don Dingledine has examined writers’ depictions of African American Civil War soldiers in his article, “The Whole Drama of the War: The African American Soldier in Civil War Literature.” He argues that regardless of their major contributions to the Union’s success, African American soldiers were “seen as issues and outsiders in the nation” during and after the War.[4] For example, James Franklin Fitts, a Civil War veteran, wrote an essay called “The Negro in Blue” in which he explains that his firsthand experience with African American soldiers dispelled his every doubt about their abilities. But he closed the essay by stating that “The negro is a curious and painful problem in our American body politic. Who shall solve it, and what shall become of him? I do not know nor assume to know.”[5]

Jayne also reveals that wounded soldiers in the U.S. Colored Hospital sang songs. In his letter, he criticized the tunes saying they were never “songs of Triumph” and sounded mournful.[6] However, these songs were prime examples of the African American soldiers’ resistance. These songs were a part of their culture, and most likely derived from hymns that enslaved people sang, which spoke of god, of freedom, and of justice, which they were actively fighting to gain. Scholar James C. Scott has called these songs “hidden transcripts” because they were evidence of “subordinated people’s discourse outside of “power-laden situations.”[7] Though Jayne could not truly tell the impact and meaning of the songs and their “sad” cadence, the soldiers found them to be culturally significant and powerful.

As a white man, Jayne had the ability to write to his loved ones and record first-hand accounts of his experiences during the Civil War. Many formerly enslaved and freed American Americans could not do so due to the system of slavery’s bans on literacy. If African American soldiers were able to write, their records were less likely to be archived. The Emancipation Proclamation, which began to end slavery was a significant change that came from the Civil War, but it is necessary that we recognize that racism and discrimination did not end. This letter shows that African American soldiers faced mistreatment and were dehumanized regardless of their triumphs and contributions. That is why their songs should be understood to be acts of resistance.

Citations

[1] Donald H. Mugridge, “The United States Sanitary Commission in Washington, 1861-1865” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 60/62 (1960): 134-135.

[2]Andrew T. Tremel, “The Union League, Black Leaders, and the Recruitment of Philadelphia’s African American Civil War Regiments,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, Vol. 80, No. (2013): 14.

[3] Samuel Ferguson Jayne to Charlotte Jayne, August 10, 1864, Jayne Papers, 1864, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan.

[4] Don Dingledine, “‘The Whole Drama of the War’: The African American Soldier in Civil War Literature” PMLA 115, no. 5 (2000): 1113–17.

[5] Ibid., 1115.

[6] Samuel Ferguson Jayne to Charlotte Jayne, August 10, 1864.

[7] James C. Scott, Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts (New Haven, CT : Yale University Press, 2008).