by Edward Lopez

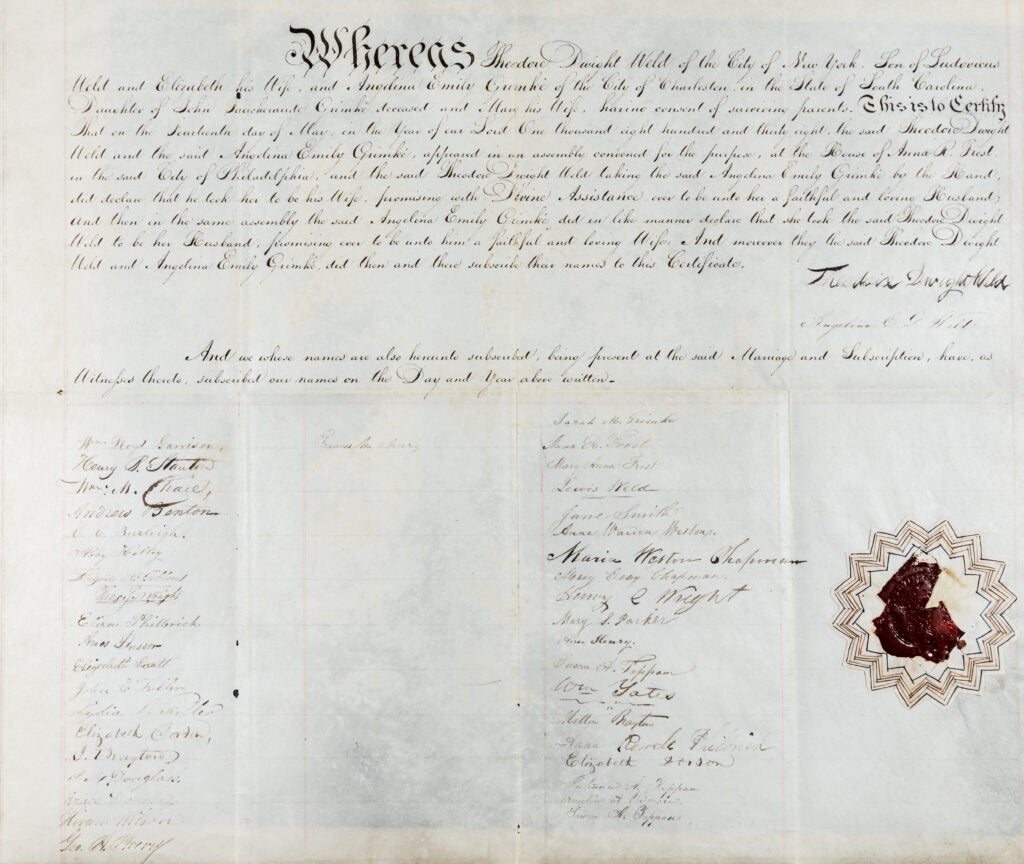

In the early nineteenth century, some Americans organized anti-slavery efforts at the local and national levels. Soon, these efforts became larger movements to abolish slavery. One abolitionist was Angelina Grimké, a Southern woman who grew up on a plantation with enslaved people. Another abolitionist was Theodore Weld whose exposure to slavery came through touring southern plantations. They first met each other at an anti-slavery conference in 1836, got married in Philadelphia two years later, and continued to work in the anti-slavery movement. Their marriage certificate and their wedding itself carries historical significance.[1] During the ceremony, they expressed their love for one another equally, they did not include any materials or goods made by enslaved people at the event, and many abolitionists, who were guests at the wedding, signed the marriage certificate.

Historian Rachel Cleves has studied marriage in early America. Her book Charity and Sylvia discusses how two women resisted social norms by living together as a married couple.[2] Theodore Weld and Angelina Grimke also resisted social norms by entering into a marriage where Angelina would be an activist outside the home. Their backgrounds informed their advocacy for anti-slavery and women’s rights. As historian Kerri Greenidge has explained in her book about the Grimké family, Theodore Weld attended the Oneida Institute where the topic of slavery could be discussed freely. As an agent of the American Anti-Slavery Society, he became part of multiple abolitionist papers, such as William Lloyd Garrison’s newspaper, The Liberator. Angelina’s parents were plantation owners and her father believed that women were inferior to men. As for religion, she never felt attached to any form until the age of 21 when she became Presbyterian. She was always outspoken and even addressed the issue of slavery at her church so many times that she was ultimately expelled. When she joined the Quaker community, she began to read abolitionist papers. The disapproval of her sisters and the community didn’t stop her, and she eventually joined the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society in 1835. Angelina wrote a personal letter to William Garrison about her determination to make changes once she joined the Anti-Slavery Society. The letter was later published in Garrison’s newspaper.[3]

Abolitionists, including Garrison, attended Angelina and Theodore’s 1838 wedding ceremony and signed their marriage certificate. Each signature demonstrates a form of resistance to the oppressive system of slavery. Having their names present on a document would expose them to hatred and risk the safety of their families. Despite these risks, their signatures show the strength and unity of their advocacy. Other names on the marriage certificate include Gerrit Smith, James G. Birney, Henry B. Stanton, and Lewis Tappan.[4] Gerrit Smith’s house was a safe house of the Underground Railroad. James G. Birney was an enslaver from Alabama who converted into an abolitionist and became a member of the American Anti-Slavery Society. Henry Brewster Stanton was a journalist who had his work published in The Liberator. He was also a member of the New York State Senate. Finally, Lewis Tappan was a co-founder of the American Anti-Slavery Society. His legal services were always of use if a formerly enslaved person found themselves in court.

The publicity that the wedding received as an anti-slavery event led some community members to burn down the newly-built town hall of Philadelphia.[5] Although it was meant to demoralize the movement, abolitionists were empowered. This marriage certificate, therefore, captures what anti-slavery resistance was like during this period of advocacy and organizing.

Citations

[1] Weld-Grimké Marriage Certificate, May 14, 1838, Weld-Grimké family papers, 1740-1930, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan.

[2] Rachel Hope Cleves, Charity and Sylvia: A Same-Sex Marriage in Early America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

[3] Kerri K. Greenidge, Grimkes: The Legacy of Slavery in an American Family (New York: Liveright, 2022) and “Theodore Dwight Weld,” Encyclopædia Britannica, November 19, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Theodore-Dwight-Weld.

[4] Beverly Tomek, “Grimke-Weld Wedding,”July 29, 2012, Universal Emancipation: Anti-Slavery and Civil Rights Movements in the Atlantic World, https://universalemancipation.wordpress.com/major-abolition-events/grimke-weld-wedding/.

[5] Greenidge, Grimkes: The Legacy of Slavery in an American Family, 84.