by Alyssa DeSarbo & Akash Fewell

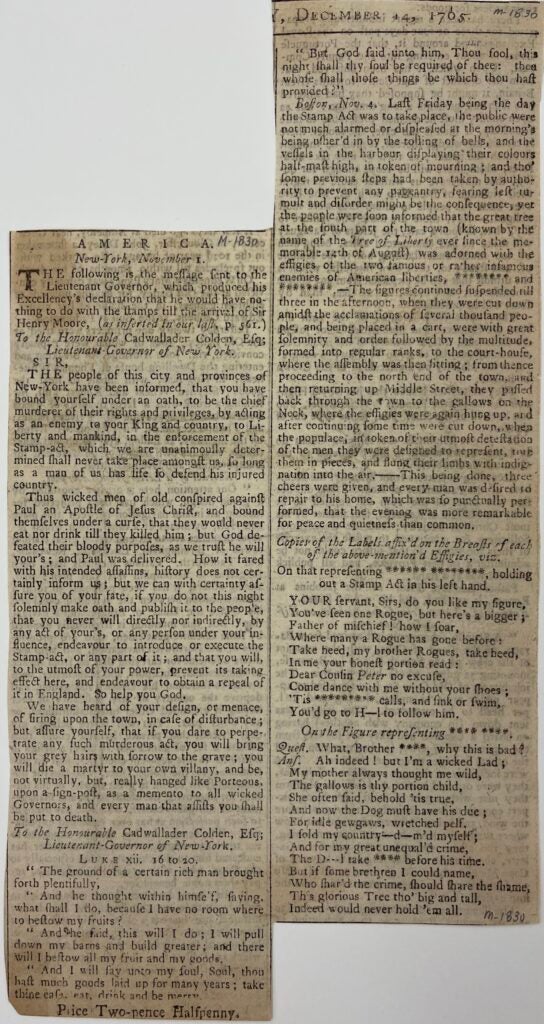

In the mid-to-late 18th century, Britain’s North American colonies battled the United Kingdom over colonial rule. One act of oppression, according to the colonial Americans, was the Stamp Act of 1765. Instituted by British authorities to compensate for financial losses endured during the French and Indian War, which ended in 1763, the Act taxed all forms of paper publication, including letters and newspapers. People living in the colonies displayed discontent with the bill, expressing resentment over “taxation without representation.” One such expression was published in a Massachusetts newspaper on December 14, 1765. This newspaper clipping features an anonymous letter that New York Lieutenant Governor Cadwallader Colden received. The letter includes threats to riot against any future action or enforcement of what was perceived as a liberty-restricting piece of legislation.[1] The newspaper also describes the events of the “Fourteenth of August,” a significant date in the colonists’ resistance against the Stamp Act. Examining this source provides more context about everyday life during the long Age of Revolutions. American colonists made daily decisions to organize themselves and resist British imperial legislation through public displays of discontent.

During a time when newspapers were the primary source of information about the state of Britain’s North American colonies, they were an integral part of people’s daily lives. The simple act of a person picking up this newspaper, reading the letter, and engaging with ideas about British imperial orders should be understood as an important piece of the greater resistance movement that led to the American Revolution. Historian Stephanie Camp, in her book Closer to Freedom, argues that everyday forms of resistance “[alert] us to the hidden origins of the most dramatic historical events.”[2] Although the letter sent to Cadwallader Colden only represents a fragment of the Age of Revolutions, it shows how the colonists began to mobilize.

The newspaper also represents how colonists living in early America formed their personal opinions about political events and people such as the Stamp Act and Cadwallader Colden. Reading the updates in the newspaper could bring colonists from Massachusetts and New York together around dislike of the new laws and disdain and distrust of the Crown and local agents. The more colonial Americans read about and participated in daily acts of resistance, the more the tensions grew, allowing for colonists to participate in larger scale resistance events such as the Boston Tea Party.

This newspaper clipping reveals that successful acts of mass resistance often come from continuous dissent over time. The events described in the newspaper clipping did not come without warning; Colden knew about the rising discontent in the colonies. F.L. Engelman’s article on the Stamp Act Riots in New York explains that this letter that threatened Colden’s life was “the culmination of over a year of discord and agitation… [against] the hated Stamp Act.” Although Engelman indicates that “neither [the letter] nor the events to follow were unexpected,” Colden exhibited complacency in the build-up to the Stamp Act’s passing, as expressions of discontent had been relatively subdued.[3]

There is some irony in how the letter addressed to Colden threatens his life while maintaining a degree of formality. By introducing Colden as an “honorable” man, the letter demonstrates that frustration was generally not towards a specific person, but was more towards the ideas that the one individual represented. Yet, the larger irony lies in the impact of the Stamp Act– if the Act was meant to keep Americans subdued, the opposite happened; American colonies ultimately united in a war of independence.

Citations

[1] Newspaper clipping, December 14, 1765, Cadwallader and Jane Colden Manuscripts and Leaf Impressions, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan.

[2] Stephanie Camp, Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 10.

[3] F. L. Engelman, “Cadwallader Colden and the New York Stamp Act Riots” The William and Mary Quarterly 10, no. 4 (1953): 560–78.