by Helena Halucha & Oak Soe Naing

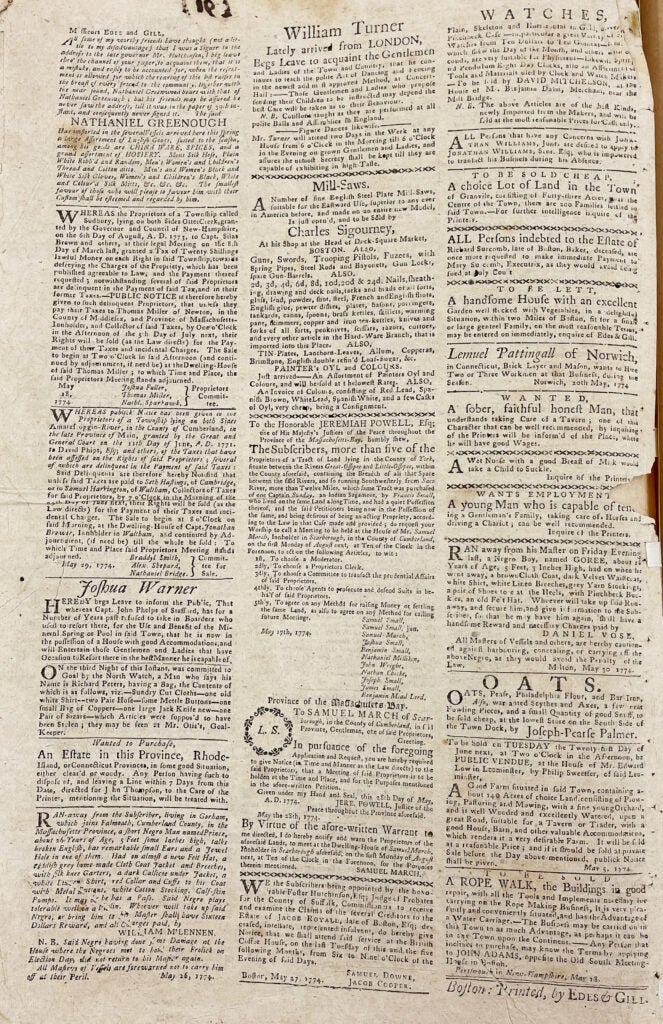

The Boston Gazette was one of the six newspapers published within the city of Boston in the 1770s.[1] The publishers, Benjamin Edes and John Gill, contributed greatly to the cultivation of independent American identity and colonial patriotism during times of increasing tension between Britain and the North American colonies before the Revolutionary War.[2] Despite the paper’s revolutionary character and spread of such ideas, at the time of publishing, enslaved people were not yet freed in the North or the South. In fact, the numbers of enslaved Africans and African Americans were exponentially increasing.[3] Some enslaved people ran away from the plantations and homes of their enslavers to resist this system of oppression and to seek freedom. This edition of the Boston Gazette from June 13, 1774 includes a wide array of advertisements from people selling various goods– houses, land, oats, and watches– alongside many advertisements seeking the return of runaway enslaved people.[4]

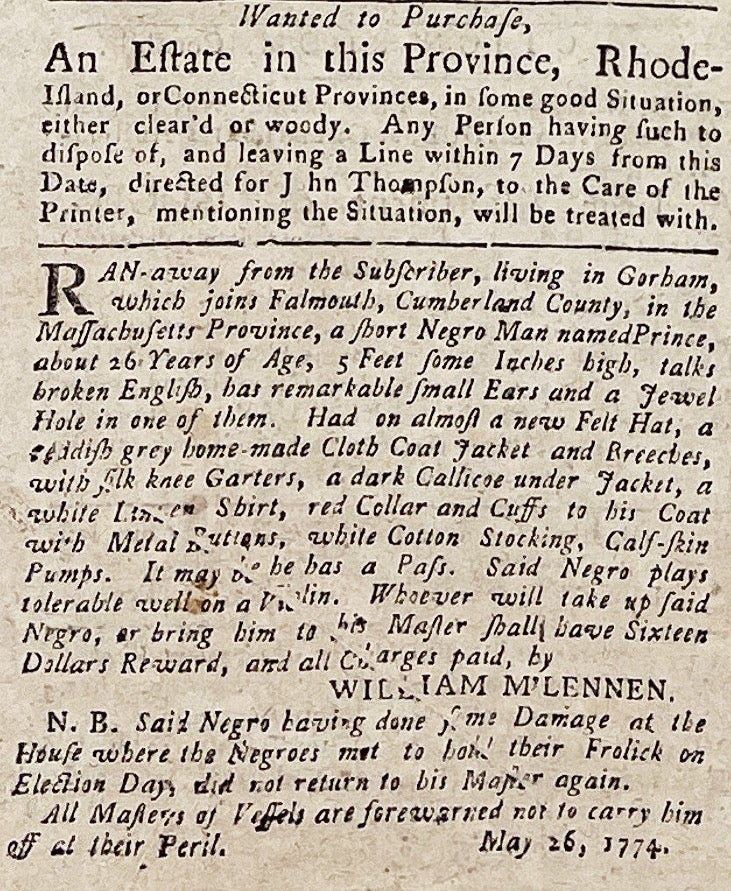

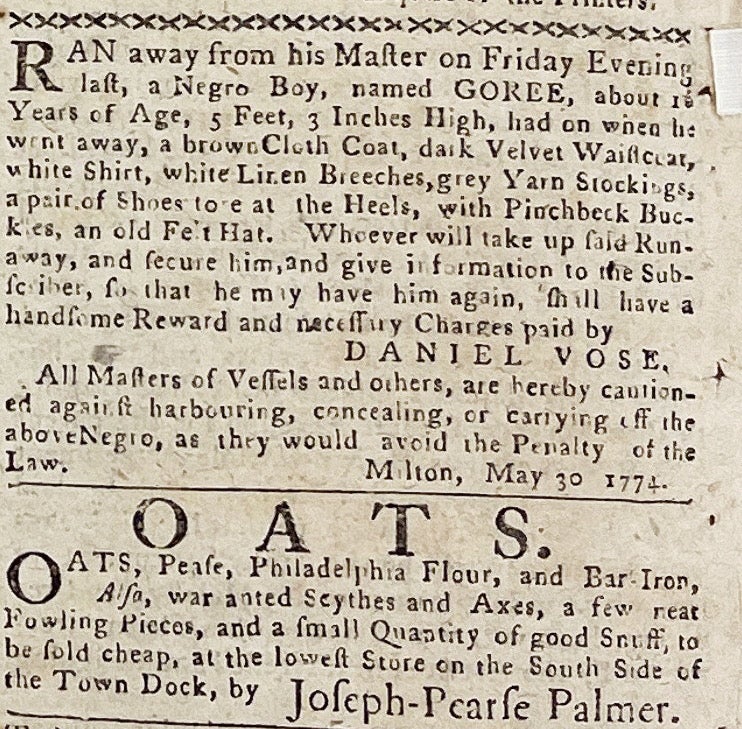

Although strikingly similar to ads for land or market goods, these ads for runaways always were different in two ways: they included a value for the capture of the runaways and they mentioned an individual or group to contact for more information, whereas other ads simply say: “for further intelligence, inquire of the printers.” This additional information within the runaway ads indicates the importance of enslaved people in the eyes of the enslavers as they were concerned about financial losses. It also demonstrates that people in the larger Boston community– printers, subscribers, and readers of the Boston Gazette– had a vested interest in the maintenance of the system of slavery at this time.

Historian Jonathan Prude has examined similar runaway advertisements in his article To Look Upon the “Lower Sort”: Runaway Ads and the Appearance of Unfree Laborers in America, 1750-1800. He has worked to decode the meanings behind these advertisements and describes them as “unimaginably rich in detail.” He explains that these advertisements were meant to draw more attention than a regular advertisement, but in a familiar way. Hence, the similarities within the spacing, size, and font which contributes to the viewing of runaways in the same manner as oats or watches. These specific advertisements found within the Boston Gazette, therefore, hold a certain significance as “they call our attention to the vital visual dimension of eighteenth-century culture…”.[5] The community was intent to facilitate the retrieval of these individuals.

Still, runaways were common based on the prevalence of these ads in the Boston Gazette. One man named Prince, who was 26 years old, ran away from his “Master” in Massachusetts Province. The advertisement specifies that Prince had run away after attending a “Frolick” with other enslaved people. Another advertisement describes a 16 year old named Goree and promises a “handsome reward” for his capture.

Historian Stephanie Camp’s book Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South helps us understand the “geography of containment” that helped define the system of slavery and the opportunities for enslaved people to resist this form of oppression. Camp investigates how many plantation owners attempted to use their power and land to control the movement of bondspeople.[8] The newspaper should be seen as an extension of enslavers’ plantations and the power they wielded; they used newspapers as a medium through which they sought control over the movement of bondspeople. They attempted to discourage other bondspeople from thinking about running away by sharing information about other runaways with the community. Nonetheless, the existence of these runaway advertisements demonstrates that despite these dangerous obstacles and risks, many enslaved people still sought freedom by escaping this “geography of containment.”

Citations

[1] “Boston Gazette & Country Journal,” Original or Reprint? A Guide to Noteworthy Newspaper Issues, Library of Congress Research Guides, https://guides.loc.gov/noteworthy-newspaper-issues/boston-gazette-and-country-journal.

[2] “Benjamin Edes | American Publisher,” Encyclopædia Britannica.

[3] David J. Hacker, “From ‘20. And Odd’ to 10 Million: The Growth of the Slave Population in the United States” Slavery & Abolition 41, no. 4 (2020): 1.

[4] June 13, 1774, The Boston Gazette, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan.

[5] Jonathan Prude, “To Look upon the “Lower Sort”: Runaway Ads and the Appearance of Unfree Laborers in America, 1750-1800” The Journal of American History 78, no. 1 (1991): 125-27.

[8] Stephanie Camp, Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004).