by Vansh Kapoor

Frederick Douglass’s oratory, writing, and activism were instrumental in the anti-slavery movement. Douglass, who learned how to read and write while enslaved, escaped slavery and became a prominent voice of the abolition movement. His persuasive writing and powerful rhetoric in works such as Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845) put him at the forefront of a movement with a goal of changing the minds of the masses.

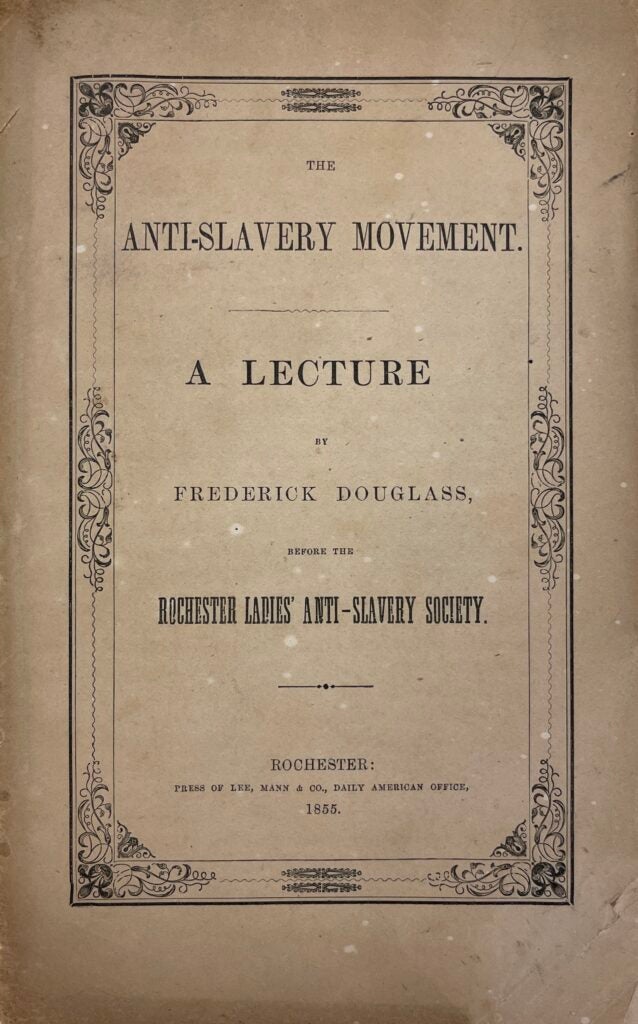

Douglass moved to Rochester, New York and published “The North Star,” a newspaper committed to “promoting the moral and intellectual improvement” of African Americans.[1] By the 1840s, many anti-slavery societies formed at the local and national levels. The American Anti-Slavery Society’s refrain was “No union with slaveholders.” Douglass responded that “As a mere expression of abhorrence of slavery, the sentiment is a good one; but it expresses no intelligible principle of action, and throws no light on the pathway of duty.”[2] In 1855, the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society, a group of northern abolitionists, asked Douglass to present a lecture on the history of the anti-slavery movement. In this lecture, he argues that abolition is in alignment with the American values cemented by the founding fathers.[3] As Douglass persuades and argues for the dissolution of an abhorrent institution, he becomes a beacon for our exploration of resistance – an exploration that extends far beyond rebellions and revolutions to encompass the gradual, persistent efforts and the power of storytelling as a form of survivance.[4]

In this lecture, Douglass dives into the multifaceted nature of resistance and the anti-slavery movement by highlighting the moral and ethical foundations upon which America was built. He draws upon the principles of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, two documents that are seen as the law of the land in the U.S., in order to emphasize the contradiction between the nation’s values of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness and the presence of slavery. In his lecture, he states, “… first, the Constitution is, according to its reading, an anti-slavery document.” Douglass dissects the rhetoric of freedom that is embedded in these foundational documents to prove that the founding ideals of the United States support the abolition of the institution of slavery. He uses these founding documents to expose the hypocrisy in society, as the U.S. public was championing individual liberties yet subjecting a large portion of its population to brutal oppression. Douglass’s ability to use the language of the Founding Fathers is an incredibly effective rhetorical technique, as he forces his audience to reflect on what America truly stands for. His argument requires audiences to critically examine the nation’s moral conscience.

In this speech, Douglass doesn’t just argue why slavery was immoral; instead, he discusses the history of the anti-slavery movement, highlighting different goals and ideals of different activist groups. He encourages everyone to participate in anti-slavery advocacy. He writes, “While it is a subject of surpassing dignity, and one upon which the wisest and best minds may be employed, it is, nevertheless, a subject upon which the humblest may venture to think and speak. As often is the case with movements pushing for “radical” social change, outsiders feel that the goals and values of the movement are hard to follow, especially when the activism is actively developing and changing. In this passage, Douglass calls upon all Americans, no matter how educated they may be, to understand the abolition movement. In this way, his lecture becomes a catalyst for a deeper societal introspection as he fosters a sense of responsibility and urgency among those who care to listen to his impactful words.

Douglass’s use of powerful words and effective rhetoric throughout his speeches and publications tie in to the idea of reclaiming a measure of control over one’s life. Resistance against oppressors allows the oppressed to take back the parts of their lives that were stripped from them – their words, their ability to act, and their time for leisure. Douglass’s speech serves as a form of reclaiming agency and challenging the dominant narratives that justified the institution of slavery. Stephanie Camp’s book explores the idea of “reclaiming a measure of control over goods, time, or parts of one’s life” as an act of resistance.[5] Douglass used rhetoric to take control of his own life. The transformative power of his rhetoric lies not only in its immediate impact on the anti-slavery movement but also as a testament to the enduring power of words in shaping the course of social and political change.

Citations

[1] “Frederick Douglass Newspapers, 1847 to 1874,” Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/collections/frederick-douglass-newspapers/about-this-collection/.

[2] Kellie Carter Jackson, “Abolition,” in Michaël Roy, ed., Frederick Douglass in Context (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021): 147-206.

[3] Frederick Douglass, The Anti-Slavery Movement, A Lecture by Frederick Douglass, before the Rochester Ladies Anti-Slavery Society (Rochester, NY: Press of Lee, Mann & Co., Daily American Office, 1855), William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan.

[4] Gerald Robert Vizenor, Survivance: Narratives of Native Presence (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2023).

[5] Stephanie Camp, Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 3-8.