by Dylan T. Wunder

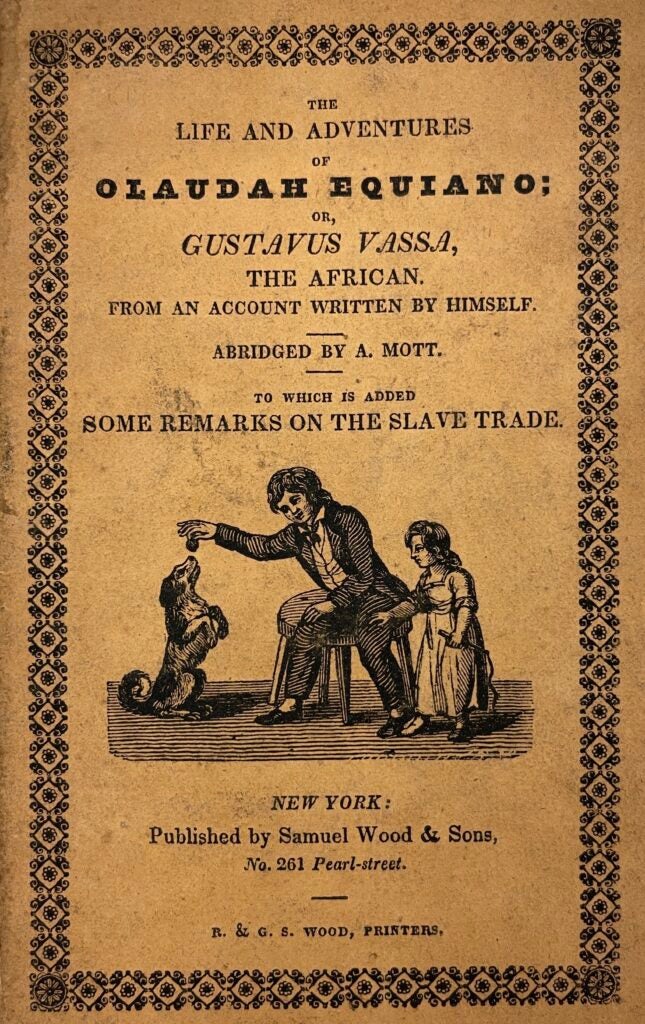

Gustavus Vassa, born Olaudah Equiano,[1] lived in what is today southern Nigeria, was sold into slavery, and was eventually able to purchase his freedom. He became well known as a trader in various ports along the Atlantic Coast of North America and wrote his autobiography entitled The Life and Adventures with the subtitle “written by himself.”[2] His autobiography is one of a small collection of self-written accounts of formerly enslaved individuals in vast early America, a collection that most recognizably includes the autobiographies of Frederick Douglass (1845) and Harriet Jacobs (1861). Vassa published the first edition of his narrative in 1789. This specific 1829 edition was abridged by an abolitionist and includes “Remarks on the Slave Trade” to highlight the brutality of Atlantic Slavery. The edition was distributed to students at the African Free School in New York. The existence of an autobiography written by a formerly enslaved person is an example of resistance because enslaved people were not allowed to read or write. The addition of abolitionist materials to Vasa’s autobiography demonstrates another layer of resistance because in New York, large-scale abolitionist movements did not exist until after 1829.

The mere existence of this book is evidence of resistance because teaching enslaved people to read and write was illegal. While enslaved in Britain’s North American colonies and the British Atlantic in the mid-eighteenth century, Vassa learned to read and write anyway. He engaged in what historian Stephanie Camp refers to as “everyday resistance.”[3] While his literacy may not appear to be an open or direct challenge to the oppressive system of slavery, it enabled him to break rules and maintain his independence of intellect and spirit. Camp argues that these minute instances of resistance are just as important in gradually defeating systems of oppression as are larger scale movements. Vassa details his various experiences from his life in Africa to his capture and subsequent sales. The primary focus of this abridgment is on his time working as a merchant along the Atlantic coast, his encounters with racism in port cities, and his relationship with his enslaver. These stories tell a tale of a man who frequently found opportunities for small-scale acts of resistance in order to make it through situations where he was frequently seen as less than human.

In freedom, Vassa did much more than write his autobiography. He has been credited as one of the first autobiographical authors to self-promote his work, and he did so with the intention of advancing his abolitionist cause. Vassa had made himself known within the London press, writing numerous book reviews, open letters, and even having a long-running feud with a defender of slavery who wrote under the pen name “Civis.” He was appointed as the King’s Commissary for the “African Settlement Project” in Sierra Leone, and was known to be a loyal British citizen.[4] By being so outspoken with his abolitionist beliefs and masterfully promoting both himself as an abolitionist figure and author, Vassa resisted a pervasive notion of and system of white supremacy in Britain, which had yet to outlaw slavery. He challenged those same notions and structures in the fledgling United States.

This edition of Vassa’s autobiography includes a section entitled “Remarks on the Slave Trade” at the end, which was added by the publishers to give students in New York a “correct idea” of what enslaved people experienced. In 1829 when this addition was created, abolitionist thought was not popular, and anti-slavery movements had not yet developed in full force. Writing and publishing these materials, therefore, demonstrate how literature has been a vehicle for resistance. Pamphlet distribution has been used to spread ideals of varying levels of popularity since the inception of the printing press in the 1450s, and as printing technology has advanced, the novel and other longer forms of text have been used to similar ends. The same is true of the abridging, publishing, and distributing of this edition of Vassa’s autobiography.

Abigail Mott, a noted abolitionist and women’s rights advocate in the greater New York/Boston area, and a key figure in the Underground Railroad, stated that her goal in editing this edition was to paint an accurate picture of the atrocities committed in the Atlantic slave trade for the students of the African Free Schools of New York.[5] The African Free Schools of New York were created in 1787 to educate and empower both free and enslaved African Americans to read, vote, and live as free people a full 40 years before the state of New York abolished slavery in 1827.[6] Students, therefore, engaged with Vassa’s autobiographical “slave narrative” and abolitionist materials while they attended this school. The narrative and its circulation was intentionally designed by Vassa to advance the cause of abolition wherever his story was read. Everything about the original autobiography, this edition, and the situation in which this edition was created is steeped in a long history of abolitionist resistance to the brutal system of Atlantic slavery.

Citations

[1] Scholars have debated which name to use when referring to Vassa. I have chosen to use the name he preferred to use as an author and abolitionist in his adult life- Gustavus Vassa. I believe that it is important when referring to any author to respect their use of their chosen name. Doing so is particularly important when examining autobiographical “slave narratives,” where the act of an author choosing a publishing name for themselves is a key part of living in freedom.

[2] Olaudah Equiano and Abigail Mott, ed., The Life and Adventures of Olaudah Equiano; or Gustavus Vassa, the African : From an Account Written by Himself (New York: Published by Samuel Wood & Sons, no. 261 Pearl-street. R. & G.S. Wood, printers, 1829), William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan. A full digitized version of this book can be found here.

[3] Stephanie Camp, Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004).

[4] Vincent Carretta and Philip Gould, Genius in Bondage: Literature of the Early Black Atlantic (Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 2015).

[5] “Key People,” Underground Railroad Education Center, https://undergroundrailroadhistory.org/key-people/#1581959372338-5e0eacf5-e44a.

[6] Anna Mae Duane and Thomas Thurston, “Learn About AFS History | Introduction,” Examination Days / The New York African Free School Collection, New York Historical Society, https://www.nyhistory.org/web/africanfreeschool/history/index.html.