by Niyatee Jain & Xixiang Luo

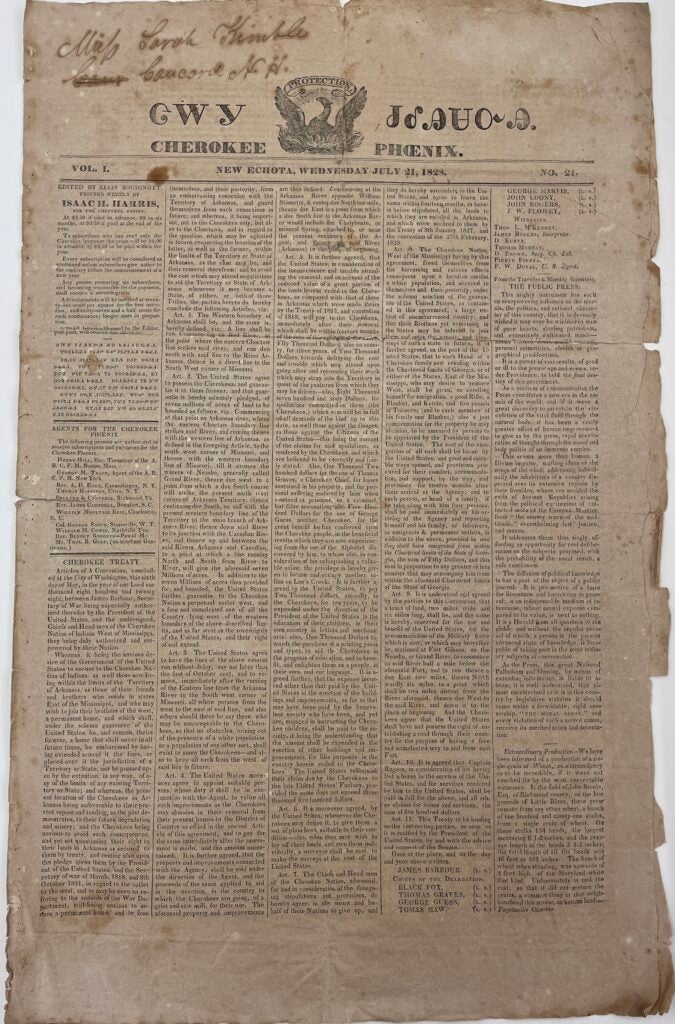

Sovereignty is defined as having authority over something, such as a piece of land or a group of people. The United States of America has fought for its sovereignty on Native lands while silencing many Indigenous voices and oppressing Indigenous peoples, including the Cherokee Nation. The Cherokee Nation sought control over their homelands and their governance in the face of a system of settler colonialism that was actively trying to eradicate them. It was through everyday materials, like the nation’s very own newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix, that leaders could express Cherokee sovereignty and emphasize principles of self-determination in the hopes of one day being accepted as an autonomous nation free from Western ideology and U.S. intervention.[1] The newspaper, which was first published in 1828, faced much adversity on local, state, and federal levels. Furthermore, the newspaper served as a means through which the Cherokee Nation spread information and advocated for themselves, whether it was through publishing editorials or simply through showcasing their ways of living. The Cherokee Phoenix is still published in Tahlequah, Oklahoma today.

Through the utilization of both the Cherokee and English languages, the Cherokee Phoenix became an instrumental part of the Cherokee Nation’s fight for sovereignty. The newspaper allowed Cherokee people to showcase their ways of living and share opinions on complex issues while also arguing that the Nation should be allowed autonomy over their lands and governance. Most of the newspaper’s published content featured national and international events, biblical passages and human interest stories, laws passed by the Cherokee Nation, and advertisements. There were also editorials or op-eds. The publication’s most important role was to inform the citizens of the Cherokee Nation about issues that affected them.[2]

Sequoyah created the Cherokee syllabary– the written form of the Cherokee language– in the 1820s, and the newspaper developed the typeface to print in the Cherokee language shortly thereafter.[3] Printing in their language, versus only printing in English, was essential to their fight against settler colonialism because the language was something that belonged to the Nation and not their colonizers. It also combatted the American government’s portrayal of them as being uncivilized. Having a newspaper that only the tribe operated also allowed for more widespread recognition because written accounts made the Cherokee Nation more difficult to erase and ignore. For example, on July 21, 1828, the newspaper published a column titled “The Public Press” from “The Traveller & Monthly Gazette,” which discusses the importance of the press on the “morals, the politics, and national character” of a country as well as its significant role as a medium of communication for the public. The column highlights the importance of a functioning press to society and describes the role a newspaper plays in informing the public and allowing for discourse through which cultures can evolve.[4]

Like other major newspapers, the Cherokee Phoenix contained editorials written by its editors who provided commentary on major issues the people of the Cherokee Nation were facing. One issue in particular was the debate about the forced removal of the Cherokee people from their lands. In 1828, the General Council of the Cherokee Nation appointed Elias Boudinot as the first editor for the newspaper at the newly established printing office in New Echota. At the time, the Nation was facing constant pressure from surrounding areas, mainly the state of Georgia, to relocate to the west of the Mississippi River, and this naturally became the central topic of the editorial pages of the newspaper. Boudinot wrote many editorials regarding the removal of Native Americans from their lands and their treatment at the hands of white settlers.[5] His editorials were significant in the fight for sovereignty as they provided insight into some of the popular opinions about the removal of Indigenous peoples.

In 1829, the tension between the Cherokee Nation and the state of Georgia escalated, which partly contributed to the polarization of leadership in the Cherokee Nation. Some parties advocated voluntary removal, believing the community, not the land, represented the nation’s sovereignty. On the other hand, a majority of Cherokee leaders maintained that relocation was a sign of weakness and a surrender of their sovereignty. The changes in editors of the Cherokee Phoenix reflected the internal divisions regarding the response to removal. As time progressed, some tribal leaders, including Elias Boudinot who shifted positions, came to view assimilation as an inevitable process, and they supported voluntary removal. To prevent Boudinot from spreading pro-removal thoughts among the community, anti-removal Principal Chief John Ross replaced Boudinot with Elijah Hicks, another anti-removal advocate. The newspaper evolved as “an instrument of the official leadership of the Cherokee Nation,” where whoever had authority over the newspaper influenced the collective definition of sovereignty.[6]

In 1835, the Georgia Guard confiscated the printing machine to “prevent anti-removal sentiments from being voiced,” leading to the nineteenth-century decline of the Cherokee Phoenix. Even so, the newspaper played an essential role in the Nation’s struggle to resist settler colonization and ensure that their Nation and their people continued to be heard throughout the United States’s eradication of their existence.

This newspaper now serves as an archive for present and future generations to hear Indigenous voices in an environment where so much knowledge of history is lost due to whitewashing and dominant narratives that center the United States. For the Cherokee Nation, the Cherokee Phoenix continues serves as an important part of their ongoing resistance against settler colonialism and their fight to ensure their Nation’s presence, governance, and culture.[7]

Citations

[1] July 21, 1828, Cherokee Phoenix, edited by Elias Boudinot and John Foster Wheeler, New Echota, GA, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan.

[2] Theda Perdue and Michael D. Green, eds., The Cherokee Removal: A Brief History with Documents (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2005).

[3] Staff Reports, January 13, 2015, “History of the Cherokee Phoenix,” Cherokee Phoenix https://www.cherokeephoenix.org/archives/history-of-the-cherokee-phoenix/article_30c25bf9-bc26-5628-9687-75e1be8581ba.html.

[4] “The Public Press,” The Cherokee Phoenix, July 21, 1828, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan.

[5] Perdue and Green, The Cherokee Removal.

[6] Angela Pulley, “Cherokee Phoenix,” New Georgia Encyclopedia, https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/cherokee-phoenix/.

[7] Staff Reports, January 13, 2015, “History of the Cherokee Phoenix.”