by Ansruta Bohra & Isaac Servin

Established in the summer of 1851 in Rochester, New York, the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society began with six women, including Susan Farley Porter as president and Julia Griffiths as secretary.[1] Within a year, the society, dedicated to immediate abolition of slavery and women’s rights, expanded to nineteen members. Initially focused on supporting the anti-slavery cause, the group later diversified its efforts by raising funds through the sale of items from other anti-slavery organizations. The proceeds primarily supported Frederick Douglass’s newspaper and the publication of anti-slavery literature. As the Society evolved, it played a pivotal role in the anti-slavery movement, engaging in activities like hosting annual festivals and establishing connections with the Underground Railroad in the late 1850s. The Civil War prompted a shift in focus, and the Society, maintaining a low profile due to its radical views, actively participated in freedmen’s education during the conflict. In the late 1860s, the Society advocated for educational opportunities for formerly enslaved individuals, although it gradually disbanded as the political landscape changed and the urgency of abolition waned with the war’s end.

These two letters from the Rochester Ladies’Anti-Slavery Society papers, respectively written by Daniel Breed and Julia Wilbur, provide a compelling window into issues faced by formerly enslaved people during the Civil War era and highlight abolitionists’ organizing efforts. Wilbur’s letter provides a vivid snapshot of the challenges those who were working to aid freed people faced as they planned to distribute supplies. Breed’s letter emphasizes education as a tool for formerly enslaved individuals’ empowerment. Together, these letters highlight how the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society functioned on the ground as members worked to abolish slavery and support freedpeople.

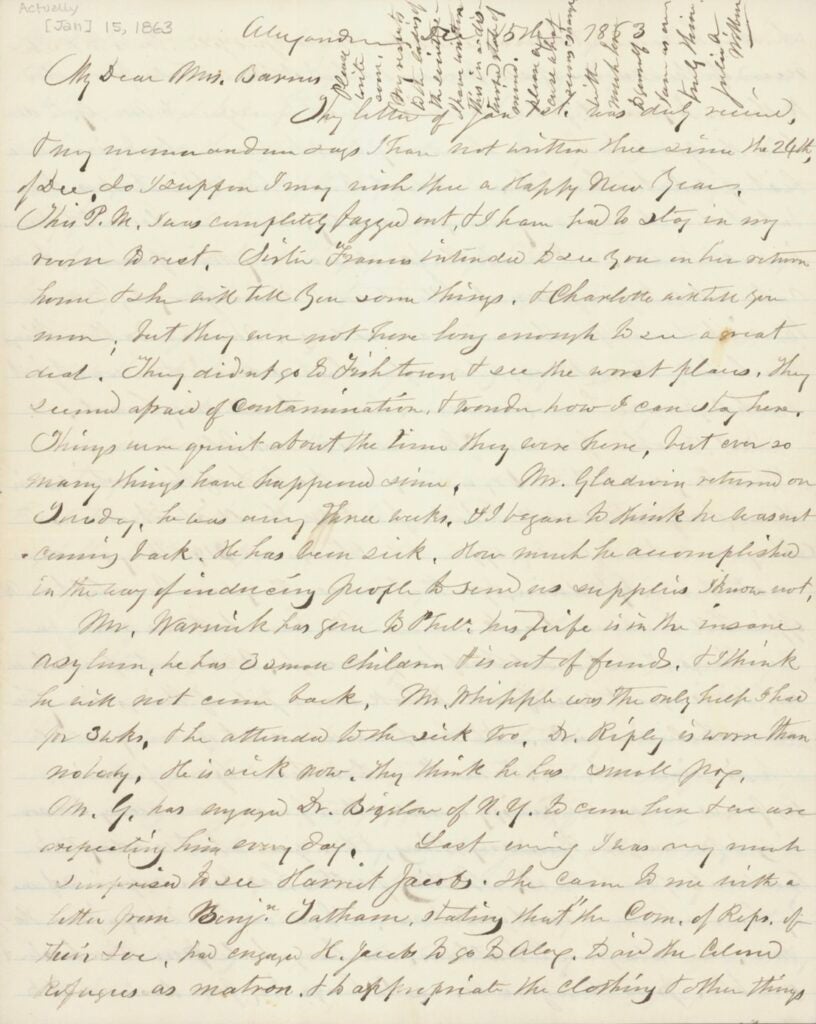

Julia A. Wilbur to Anna M. C. Barnes, January 15 – January 17, 1863

This letter, written on January 15, 1863, immerses us in the intricate challenges faced by relief workers during the Civil War, providing a vivid snapshot of the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society’s pragmatic and impassioned resistance against slavery. Driven by an unwavering commitment to the abolitionist cause, the society strategically organized its efforts to aid people who escaped slavery and sought refuge among Union soldiers. Wilbur wrote this letter days after President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation.[2]

The heart of the Society’s resistance lay in the tangible actions undertaken by a network of women and allies engaged in purposeful correspondence. In Alexandria, Virginia, where Wilbur composed this letter, Society members worked with contrabands– enslaved people who had escaped to Union lines. Wilbur acknowledges the “insult & abuse” the freedpeople were receiving from the white soldiers. The letter sheds light on the day-to-day, on-the-ground organizing efforts in this environment, which illustrates members’ monotonous yet crucial actions. In these seemingly mundane tasks—procuring supplies and overseeing clothing distribution—the steadfast resilience of the abolitionist movement comes to the fore.

The letter indicates the process for giving aid in the form of goods: “As far as we can we satisfy ourselves that persons are needy & deserving before we give them any thing, & then give what is adapted to their wants if we have it,” writes Wilbur.

In this letter, two prominent abolitionists who had escaped slavery themselves, Harriet Jacobs and Frederick Douglass, emerge as central to the Society’s initiatives. Harriet Jacobs assisted fugitives by overseeing clothing distribution. Efforts to distribute clean textiles were significant because of a recent smallpox outbreak. Wilbur writes, “She can do these things much better than I can, & I am glad she has come, & we want just such a person here. I welcome her with all my heart.” Frederick Douglass assisted with providing supplies to aid freedpeople.

Specific contributions of the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society should be better appreciated, particularly because of the gender dynamics within the broader abolitionist movement.[3] This letter, which focuses on practical initiatives and expressions of gratitude for the Society, underscores the significance of women’s roles in sustaining the antislavery movement.

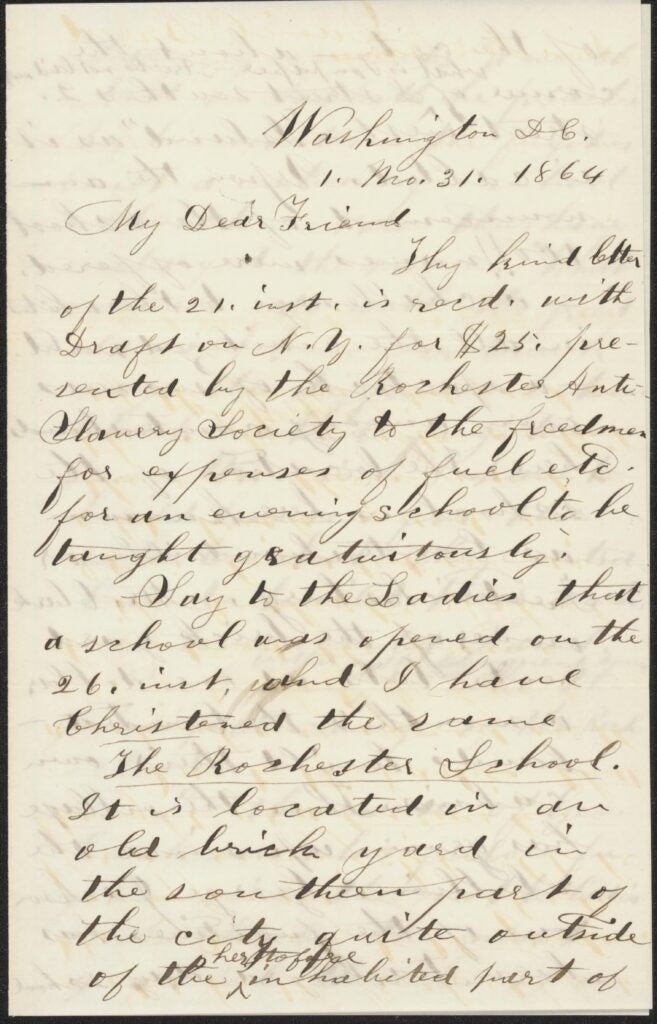

Daniel Breed to Anna M. C. Barnes, January 31, 1864

In early America, the movement of enslaved people was highly restricted by their enslavers. Enslaved people were only able to leave the plantations or homes of their enslavers if they were granted a pass containing information of their exact and expected time of arrival and departure. Despite these strict conditions, enslaved people reclaimed their ability of movement. Historian Stephanie Camp explains how spatial resistance played an important role in resistance to this system of oppression. The term “frolic” was coined to signify large scale gathering of enslaved people in a social setting. These gatherings sometimes paved the way for other spatial acts of resistance, including running away. During the Civil War, some people who ran away joined the Union army and found refuge as fugitives in contraband camps. Freedpeople could then gain an education, which was prohibited under slavery.

In this letter, Daniel Breed outlines to Anna Barnes, a member of the Rochester Ladies’ Society, the need for aid for formerly enslaved people who had escaped and found refuge in contraband camps. Breed relays a message from another person involved in giving aid to fugitives who said: “I have to build houses for the whites but the contrabands build their own.”[4] This implies that freedpeople played active roles in building infrastructure.

In addition to advocating for the end to slavery, the Rochester Ladies’ Anti- Slavery Society provided aid in the form of monetary donations. Breed mentions the opening of a new school in the south side of Washington D.C., which was funded by the Rochester Ladies Anti-Slavery Society. Breed states that George Jackson, one of the fugitives, has been teaching at a school and charging 50 cents per month. “By his exertions,” writes Breed, “the fugitives built a cabin for school & church.” Efforts to provide educational opportunities for the formerly enslaved were not only made by the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society, but also by the freedpeople themselves. It required an effort of both parties to further educational opportunities with the society providing the financial support and the freedpeople facilitating the process.

Scholar Vota Risley has examined the publication of anti-slavery newspapers and the role they played in spreading abolitionist thought. A reviewer of his book, Frank E. Fee, argues that the book “does not fully develop the roles that women played in the abolitionist press.”[5] This letter, which reveals the non-press-related efforts of anti-slavery organizing, can help correct this general gap in knowledge about women-led organizations. This letter demonstrates how much effort the members of the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society put into developing the infrastructure and the education efforts of the abolitionist movement.

Citations

[1] Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society papers, 1848-1868, William L. Clements Library Finding Aids, University of Michigan.

[2] Julia A. Wilbur to Anna M.C. Barnes, January 15- January 17, 1863, Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society Papers, Box 1, Folder 40, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan.

[3] Frank E. Fee, “Abolition and the Press: The Moral Struggle Against Slavery” Journalism History 35, no. 2 (Summer, 2009): 114. Fee’s article is a review of Vota Risley, Abolition and the Press: The Moral Struggle Against Slavery (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2008).

[4] Daniel Breed to Anna M.C. Barnes, January 31, 1864, Rochester Ladies Anti-Slavery Society Papers, 1848–1868, Box 1, Folder 60, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan.

[5] Fee, “Abolition and the Press: The Moral Struggle Against Slavery,” 114.