by Ari Roth & Lilly P. Vydareny

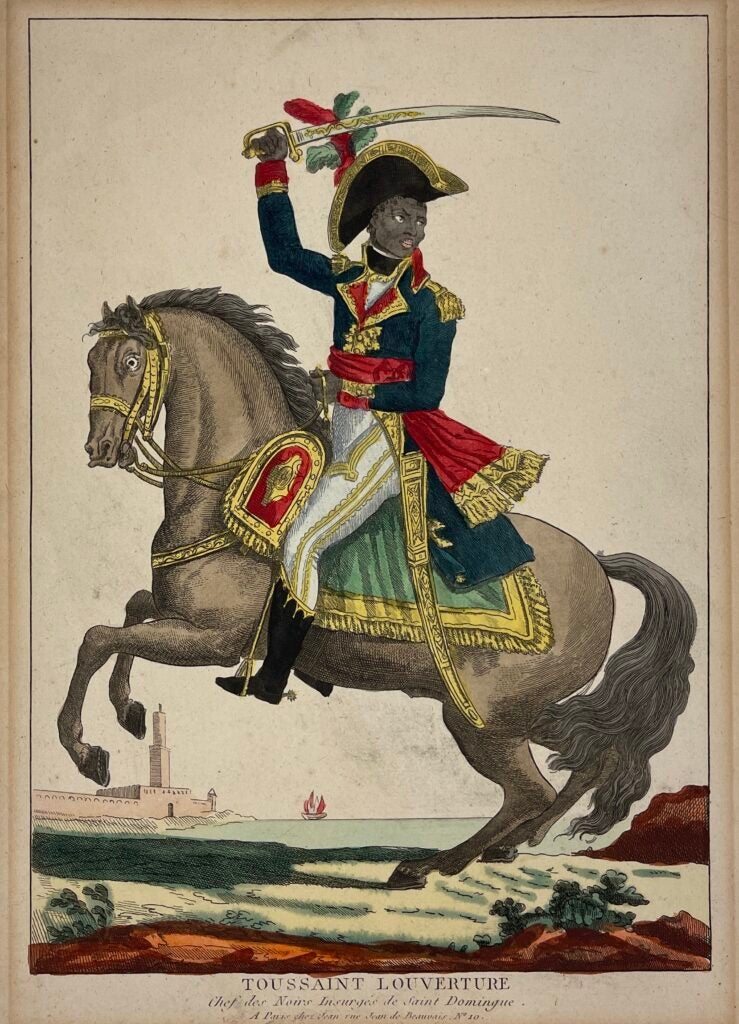

Inspired by the French Revolution, enslaved people on the island of Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti) began participating in decentralized revolts in 1791. The burning of plantations and the killing of enslavers evolved into full-scale war with the European forces that occupied the island. Toussaint L’Ouverture, who was enslaved for much of his life and became a free man who oversaw his former enslaver’s plantation, emerged as the leading figure of the Haitian Revolution. L’Ouverture quickly distinguished himself as a skilled strategist and leader. He eventually gained control of the whole island and authored an abolitionist constitution for the new nation of Haiti. His power and reputation were built on his godlike image that developed due to his leadership and his role in Haitian people’s emancipation. This portrait of L’Ouverture calls him “Chef des Noirs Insurgés de Saint Domingue (“Leader of the Black Insurgents of Santo Domingo”).[1] The print reveals the clash of European stereotypes of African peoples’ appearances and syncretic Afro-Caribbean identities that emerged from enslaved Africans’ resistance to European colonialism and exploitation. The print also reflects the commerce and communication among seamen in the Caribbean that established an ‘echo chamber’ for revolutionary and Enlightenment ideals.

The print’s depiction of L’Ouverture’s features indicate that his face was most likely based on stereotypical perceptions of African peoples’ appearances. During this time, portraits of respected military leaders were not uncommon, however, the subjects were predominately white men. The artist likely did not have experience in depicting African people realistically, as many depictions of Africans were racist caricatures – the dark, gray-black shade of his skin and the bizarre shaping of his nose and lips reflect European conceptions of Africans’ appearances, which were frequently and notably distinguished from those of Europeans.

The rest of the portrait reveals L’Ouverture’s defiance against racial hierarchies and imperial power. The depiction of a free Black man leading a rebellion of such magnitude and success indicated that he commanded respect and admiration from Europeans and Haitians alike. His clothing and accessories – his saddle, sword, and dress– reflect the strong influence of European culture and governance on emerging Caribbean identities. The style of clothing was clearly influenced by European military dress, which can easily be identified by the highly ornate collared coat and pants. Today, the Haitian flag retains the rich blues, reds, greens, and yellows associated with European monarchy. Historian Laurent Dubois, who has examined connections between colors, patterned practices, and styles of self-presentation, helps us understand how the printer presents L’Ouverture in this portrait. Dubois labels the tendency of Haitian insurgents to incorporate characteristics of European monarchy and elites (such as “gray and yellow” and “royalist symbols”) as “insurgent royalism.” He explains that “many leaders were themselves understood to be ‘kings’[.]”[2]

As scholar Nigel Bolland has argued, other aspects of Haitian culture today are rooted in the unique and rich blends of both traditional African and European languages, religions, and practices. Haitian Creole, for example, is the primary language spoken by Haitian people that is a blend of French and African languages. Syncretic religions, such as Vodou and Candomble, which mix traditional African religions with features of Christianity and European theology, also developed in the pre- and post-colonial Caribbean.[3]

Although L’Ouverture dominates the foreground, the background of the portrait offers rich insight into the ways in which revolutionary ideas spread throughout the Atlantic Ocean. The boat behind L’Ouverture sailing off into the Caribbean Sea mirrors the continuous naval commerce between growing European colonies. The large fort that also fills the backdrop indicates the establishment of the island of Saint-Domingue as an important location of goods and information exchange. Through commerce and contact between seamen, as historian Julius Scott has argued, the Atlantic Ocean acted as an echo chamber for the spread of revolutionary ideas. Free African seamen and traders in colonies such as Saint-Domingue and Jamaica circulated gossip and rumors about the French Revolution and the end of slavery, which allowed for the rapid spread of revolutionary ideology and news of impending war in England and France.[4] The portrait, therefore, puts L’Ouverture at the center of these Atlantic debates about identity and freedom.

Citations

[1] “Toussaint Louverture: Chef Des Noirs Insurgés de Saint Domingue,” A Paris chez Jean. rue Jean de Beauvais. No 10 : Jean, Possibly between 1800-1802, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan.

[2] Laurent Dubois, “‘Our Three Colors’: The King, the Republic and the Political Culture of Slave Revolution in Saint-Domingue” Historical Reflections / Réflexions Historiques 29, no. 1 (2003): 83–102.

[3] Nigel O. Bolland, “Creolisation and Creole Societies: A Cultural Nationalist View of Caribbean Social History” Caribbean Quarterly 44, no. 1/2 (1998): 1–32.

[4] Julius S. Scott, The Common Wind: Afro-American Currents in the Age of the Haitian Revolution (United Kingdom: Verso, 2018).